By Dwaine Hill

When B.F.A. fashion design student Diego Rivera moved to San Francisco from Miami to pursue an education in fashion design, he embarked on a period of self-reflection. The homogenized version of San Francisco left him both longing for and discovering a new appreciation of the Latino upbringing and culture he grew up with. He recalls visiting friends, their families new to the U.S. from Cuba, Venezuela, or Nicaragua, all speaking Spanish. He remembers nights spent at clubs playing nothing but reggaeton or cumbia and going to the 24-hour bakery for pastelitos (a Cuban pastry) and Cuban coffee.

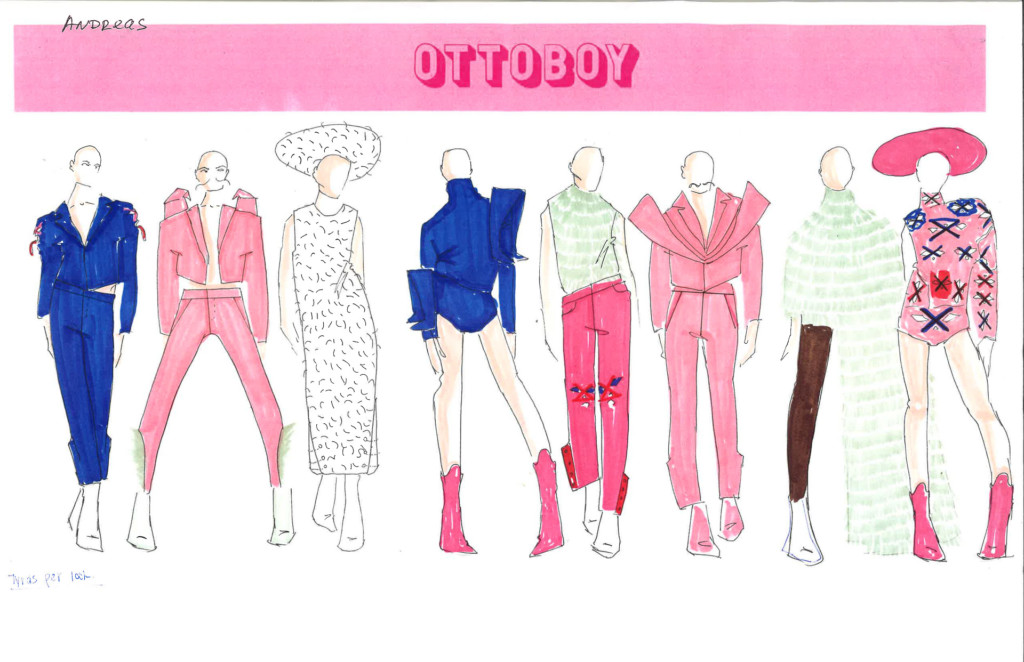

Rivera’s thesis collection, “Ottoboy,” is an embodiment of that and more. It pays homage to his father, Otto, and tells the tale of growing up as a child in El Salvador. When they were young, Otto and his brother would create fantastical worlds in their minds to escape the harsh reality of civil war. They would lose themselves in the innocence of childhood dreams, away from being ostracized and marginalized. Rivera’s collection lives in these worlds. It’s a place clothed in a glamour of his own making, a grand illusion to escape the humdrum of our modern woes.

Each piece in the collection drips with Latino influences. Silhouettes take form from mariachi hats; the outline of a sombrero brim turns into an architectural shoulder. “It’s a symbol of masculinity,” the Academy of Art University School of Fashion student explained. “The bigger the hat, the more of a man you are.”

Rivera further explored this construct of masculinity through soft pinks and metallic brocades, together with stretch leggings printed with an image he took of his own leg hair. Overall, it’s a collection that is tailored and sharp, where clean lines mix with ruffles or tulle.

With the Virgin Mary being a central figure in Catholicism, it’s “la capa de la Virgen” or “the Virgin’s cape” that is Rivera’s pièce de résistance. Layers of seafoam green tulle cascade to the ground, draped asymmetrically, one arm free from constraint.

Customs and traditions blend to create a fusion of pride that teems within Rivera’s collection. He merged parts of his culture, dignifying them, remembering them in a most extravagant way. “It is my love letter to El Salvador,” Rivera said. “This idea of a home I never got to live in.”