By Tyler Callister

Filmmaker Nirav Bhakta starts his creative process with a simple question.

“I always ask myself, ‘What do you have to say?’” he explained. “My golden rule is, ‘Only speak if you have something to say.’”

For Bhakta, a 2017 Academy of Art University School of Architecture M. Arch graduate, his simple question seems to have paid off big time.

At a young age, he’s already begun to hang film awards from his mantle. He’s earned nods from HBO (first place in the 2019 “Asian Pacific American Visionaries” contest), the non-profit organization Visual Communications (winning an “Armed With a Camera Fellowship for Emerging Media Artists” in 2020), and most recently, CBS (first place in the 2021 Leadership Pipeline Challenge for his film “To The Letter”).

Despite the accolades, Bhakta hasn’t let them go to his head. Soft-spoken and humble, he downplayed the awards, insisting that it’s about something bigger.

“I don’t take them seriously,” he said. “I think what matters most is the social impact… I truly, truly believe that the stories we decide to tell are bigger than ourselves. That’s my foundation.”

Social impact clearly plays a major role for Bhakta, as almost all his films demonstrate. His HBO-awarded film “Halwa” tells the story of an Indian American woman living in an abusive marriage; his 2020 film “Thank You, Come Again” tackles issues of hate against immigrants; and his most recent piece, “To The Letter,” explores the lives of unhoused children.

But even with social impact in mind, Bhakta comes back to the foundations of his creativity. He waxes philosophically about what drives his process, again returning to a simple question.

“‘What is my intention?’” he asked aloud. “‘Can my intention elevate this story in front of me?’ If it can’t, then that story is not wanting to be told.”

Bhakta dove deeper into what he means by “intention” via email.

“Intention comes from a want of being centered to access a place of honesty and truth,” he wrote. “I believe all powerful storytellers gain breakthroughs when they are able to reflect a raw human honesty in their narratives. It’s the universal experience in the unsaid.”

In many ways, Bhakta’s deepest intentions may arise from his own story—he is of East Indian descent but was born in Panama. In the early 1990s, his family fled the country to escape the violent drug trade. They eventually settled in Houston, Texas, where his father and mother ran a motel.

As a young man, Bhakta’s roots in film started with theater and Indian dance.

But when Bhakta showed up at the Academy to earn his master’s degree, he majored in architecture, not film. As the son of immigrants, he said he felt pressured to seek a more “practical” means of making a living. The compromise? A degree in architecture.

“Education was a very important and integral thing for my family,” he said. “Architecture was my closest creative outlet.”

But his deepest creative intentions burst within. Film called to him, and he soon found himself taking classes in the Schools of Acting and Motion Pictures & Television at the Academy.

“Ultimately, architecture became my excuse to study filmmaking and acting,” he said with a laugh.

No matter the medium, Bhakta seems to bring it all back to having something to say through his art. “If you don’t have something to say, that means you are not attached to the story on a cellular level, where you understand these characters, you understand this world, even though it’s not from your experience,” he said.

“To The Letter” wins CBS award

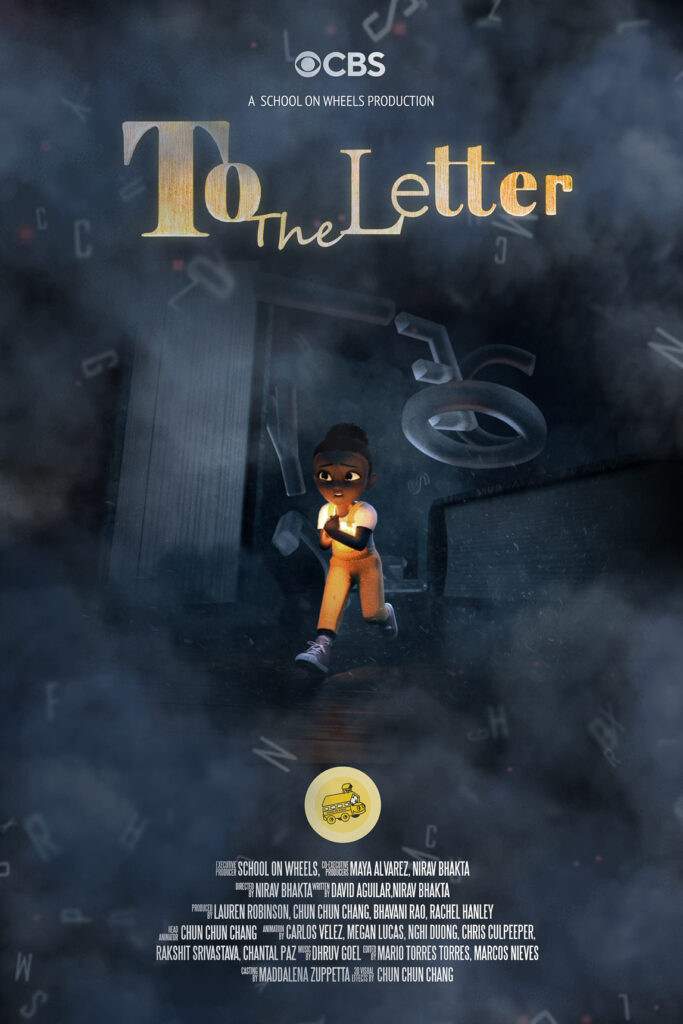

Bhakta’s latest success, an animated short called “To The Letter,” captures Bhakta’s trademark combo of art with a social cause.

The film, a digitally animated Pixar-like cartoon, works as a promotional ad for Los Angeles non-profit School on Wheels. In July of 2021, the film won first place prize in the CBS Leadership Pipeline Challenge, earning the non-profit group a $10,000 donation. That’s a significant contribution to the 30-year-old group that provides reading tutors to unhoused children in the Los Angeles area.

To make the film, Bhakta insisted on doing research to make a deep connection with the children it affects.

“Research is a big part of my process, talking to people who have gone through lived experiences,” Bhakta said. “Whenever I show people from underrepresented communities on screen, I hope that I can do their voice and their experience justice.”

To accomplish this, Bhakta and his team spent time with unhoused children and their tutors at School on Wheels.

“We quietly sat in on tutoring sessions and got to see how the tutors are like mentors to these children… it was a really beautiful experience,” Bhakta said.

The film’s composer and sound artist Dhruv Goel visited L.A.’s Skid Row—a neighborhood known for its large unhoused population—where he recorded actual sounds from the street to use in the film.

In the final product, the team’s intimate research comes to life. “To The Letter” begins with a scene showing an unhoused girl struggling to read. She sits alone in a library, grasping at letters floating off the page. She soon finds herself wandering a dark street, as police sirens blare in the background. She falls to the ground in tears, but is soon rescued by a School on Wheels tutor who holds the illuminated words “believe.”

While Bhakta has made many live-action films before, he has never done animation. Luckily, as a former student of the Academy, he had accumulated a vast network of creatives—including talented animators.

Bhakta’s team, an X-Men-like group of animators across the U.S., included many alumni from the Academy’s School of Animation & Visual Effects: Chris Culpepper, Carlos Velez, Megan Lucas, Nguyet Nghi Duong, and Chantal Paz.

Culpepper, a 2020 graduate and one of the lead animators on the film, worked remotely from North Carolina. He said the process of watching it slowly come together, then finally come to life, was exciting.

“To see it all come together, finished, it was mind-blowing,” Culpepper said. “We didn’t hear the music until the final rendering. It was wonderful.”

Culpepper said that they used the voices of the actual children from the School on Wheels program as well as some of the children’s drawings in the end credits for the film.

The awards and recognition the film received are a “dream come true,” said Culpepper.

But Bhakta, who seems to enjoy talking about his ideals as much as the film’s mechanics, emphasized art over awards. He remained steadfast that the artistic intention behind the film was his ultimate goal.

“All that matters as a filmmaker is that your film spoke to one person somewhere in some corner of the world,” Bhakta said. “Awards are great… but what’s most important is that connection with your audience.”