By J. Elliott Mendez

In the heart of San Francisco’s vibrant Mission District, Manny’s has become a hub for showcasing diverse and thought-provoking art as well as insightful conversations. Recently, the venue welcomed artist and photographer Rachelle Steele, whose captivating works continue to leave indelible marks on whoever would dare to gaze.

If her name sounds familiar, it should. She has won award after award for her work and traveled near and far to capture still images that somehow encompass the complexity of a moment. She’s been named the International Portrait Photographer of the Year for three years running—a title that she shares with only 100 other people in the world. She is a sister, a mother, a veteran of the United States Navy, and an Academy of Art University School of Photography alumna who sees life in layers.

Steele’s story is a hero’s journey. To understand it, the best place to begin is “in medias res”—in the middle.

“I was stationed in Mississippi, but we didn’t get evacuated because that was our base,” shared Steele. “I ended up going with the U.S. Navy deep-sea divers and the [U.S. Army soldiers] and photographing a lot of body recovery. I never shot after that. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had gotten extreme photographic PTSD from that.”

It was 2005 when Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana. Steele was stationed at a base in neighboring Mississippi with her children. Though she had no formal training in photography, she always considered herself a “shutterbug.” When her natural talent was discovered, she was assigned to visually document recovery efforts. This meant long hours in the water, absorbing the death and destruction in Katrina’s aftermath firsthand.

“It was a massive effort. I knew for a fact no one was documenting it, and that was such an epic moment on a lot of levels. From my point of view, this was intense. I’m going with the [U.S. Navy] Seabees as they’re going house to house to house, counting bodies, clearing the roads that have cars full of bodies. I just had this feeling that it needed to be done.”

It would be another five years before her hands would touch a camera again. Not until she was gifted one with a not-so-subtle note of encouragement from a friend, “Time to start shooting.”

“Every time I picked up my camera, it was this excruciating process to the shoot. I’d do the shoot. Then I would start crying. I was so dysregulated. My work was looking really good, but there was just no way I could do it because it was just so intense.”

However, after winning second place in a national photo competition, she was convinced that she could, in fact, “do this,” but she was going to need real training. After Googling the “best photography program,” she landed at the Academy.

“I could feel, through the process of having my brain getting trained. And [with] a certain couple of [instructors], I could feel my brain unlocking and forming new pathways. I could feel myself calming down a little bit photographically and [developing] the ability to express visually the things you don’t really have words for.”

Fast forward to 2020. After having built a decent-sized portfolio of images specifically for showcasing, Steele shifted gears to do an intense project during the initial weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. The project received international coverage and put her on the map. She completed her graduate program at the Academy and moved on to her next big project, Morocco.

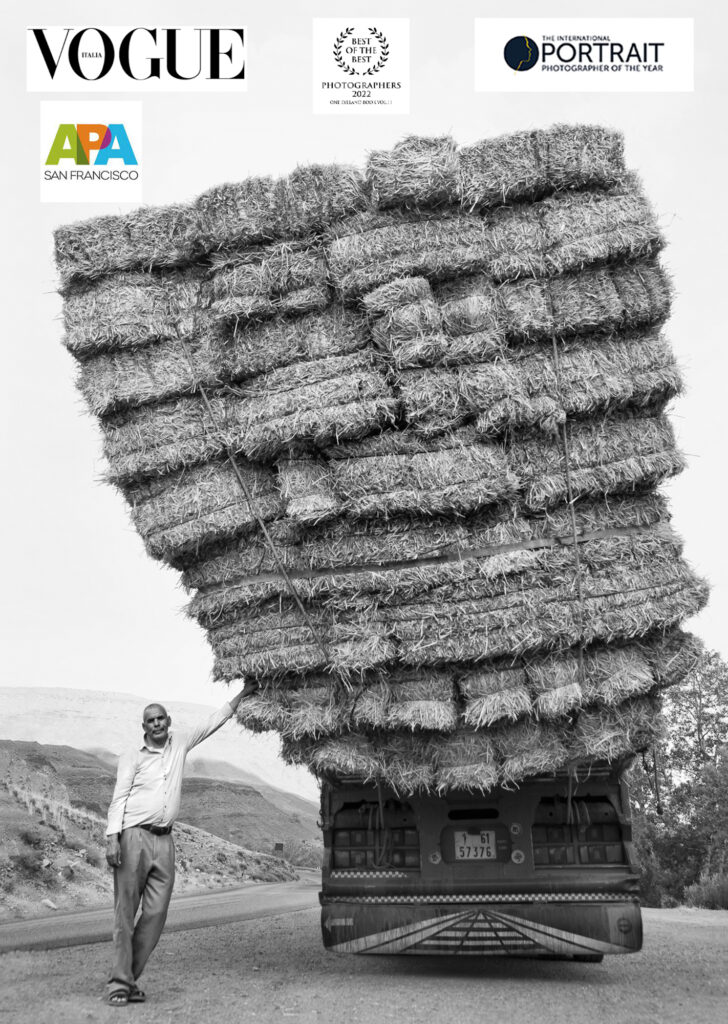

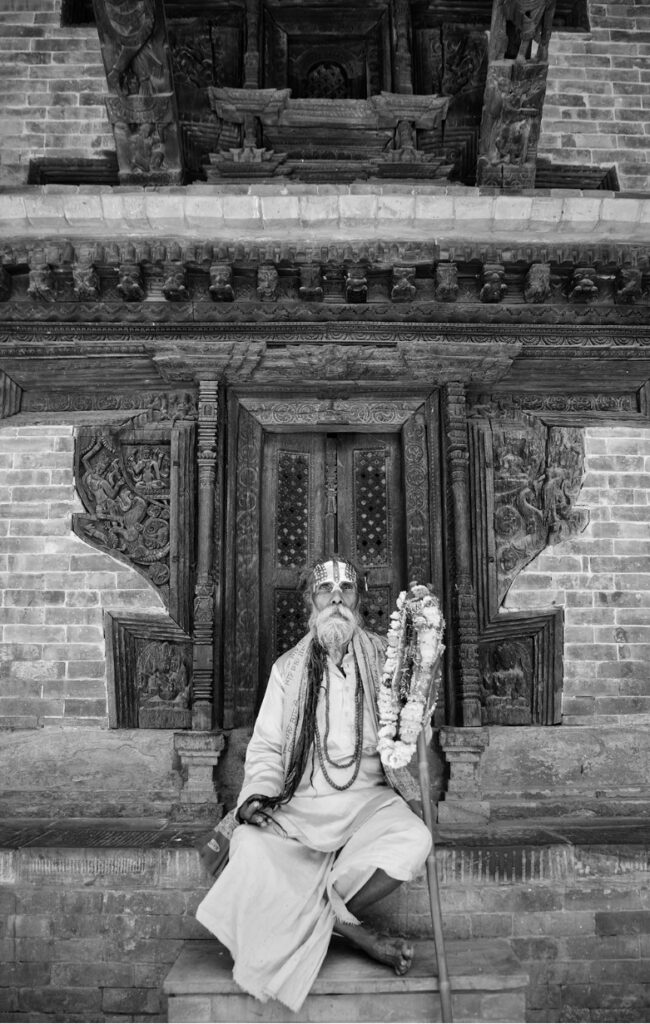

Steele completed a residency program, creating the body of work “Scent of Morocco,” before moving on to do a solo exhibition in Tetouan, Morocco. It was at this point that the photographer finally felt ready, that her emotional, mental, and physical self were back in alignment.

“Scent of Morocco” is one of the works featured at Manny’s. The other is “Early Morning Incense.” Steele calls it “Master Works,” a collection of 10 photographs (five from each body) which she says are her personal favorites.

“[For the last 15 years], I’ve only been exhibiting at super intense galleries. I was a little nervous about Manny’s because I didn’t know if people would feel like I was wasting their time,” Steele admitted. “Manny’s is so rad. [It’s] a little hub, and I’m so grateful to have my work there because tons of people are seeing [it].”

There’s an obvious connection between the environments Steele enters, the emotional burden she bears going to document these moments, and her time in Hurricane Katrina. But there is another, less visible throughline that drives her—a promise to live hard.

To date, she’s lost four shipmates to suicide, one while she was still in school at the Academy working on her master’s project, “Shark Skin Boots.” That project was originally titled “More Than a Dead Junkie,” a reference to her late father, who was murdered when she was 10. It was her way of telling her community and the world that he was more.

This is what Steele is trying to get at. When you take in her images, you see more than a Moroccan woman who has never been photographed, more than veterans lost to suicide, more than bodies cleared after the storm, more than a dead junkie, and more than an artist who has overcome PTSD. She is asking you to see the complexity of that single moment and then see yourself. She is asking you to live—hard.

“There’s so much darkness. I want them to live hard. I do. I want people to experience life,” said Steele. “Maybe when the unknown viewer is seeing my [work], they’re recognizing something in [themselves]. Maybe in that microsecond, they’ll picture themselves in that environment, their response to that environment, [and] who they would be in that environment. They’ll recognize their own humanity. Maybe they recognize a little gratitude that they need to have in their head.”