By Nina Tabios

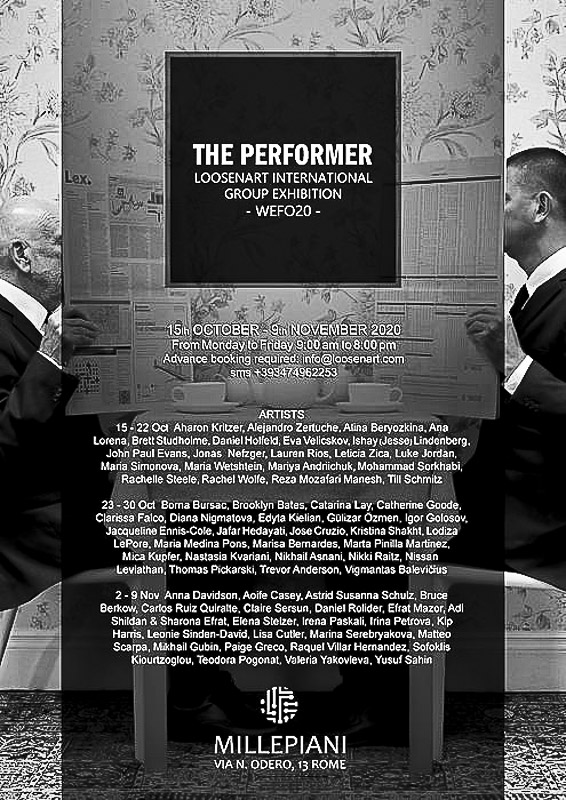

From Oct. 23 to 30, Academy of Art University School of Jewelry & Metal Arts (JEM) student Trevor Anderson’s striking sculpture and art piece will be on display at the Millepiani Gallery in Rome, Italy.

The featured piece will appear as a large-scale print, where the five steel clothespins named “Remember Not To Forget” are pinned to various points on Anderson’s grimacing face. Part sculpture, part performance art, the 2020 M.F.A. graduate said it is all part of his exploration of masculinity, conflict, and violence.

“My JEM wearable sculpture work is halfway between performance art and the actual physical artifact that I am producing,” Anderson said from his home in San Diego, California. “Both things are the art themselves—the gesture of the performance and the actual physical piece.”

“Remember Not To Forget” was one of several handcrafted items Anderson made for his provocative thesis collection. Using Damascus steel and Kevlar cords, Anderson created unconventional masks, hoods, pacifiers, and shackles that he hopes ignites new modes of thought around maleness and classic male archetypes.

“My pieces aren’t conventionally beautiful or attractive in the sense that I’m not attempting or setting out to make a line of jewelry to sell, they’re much more on the conceptual side,” explained Anderson. “I would hope, at least in the moment, that [people are] engaging with the piece and empathizing with it. To take away just a little feeling from it and maybe it pops into their mind later and revisit it—‘What was that really about? How did that make me feel? How do I feel about what they were trying to say?’”

In a recent interview, Art U News spoke with Anderson on his journey to creating conceptual, challenging art, and the complex topics embedded in his work.

How did the opportunity to show your work in the Millepiani Gallery come about?

So many of us artists are having to adapt in this pandemic age, so we’re seeing digital showings become more and more prevalent. As I was applying to tons and tons of open calls for entry, I kept coming across digital showings. I was accepted to a number of them and through one of these digital salons that I participated in, I was able to open the door and make a connection to having this physical showing through [the show’s] hosting organization called LoosenArt. I participated in a few of their digital showings, and then, ultimately, they reached out to me to participate in the physical showing for an exhibition they’re calling “The Performer.”

Can you tell us about the piece, “Remember Not To Forget”? What inspired it?

The broad topic of my M.F.A. thesis surrounds the idea of exploring modern male archetypes and how archetypes change over time, especially in terms of classic male archetypes that are generally thought of as dominant or forceful. With that notion, I approached changing archetypes of maleness from the other ends of the spectrum, looking at the idea of trauma or personal cathartic gesture.

In the case of the “Remember Not To Forget” piece, it also follows that same suit in that it represents a sense of loss of empowerment. The clothespins are generally a very domestic object—an everyday thing—and they have their own identity and meaning that is often associated with cleanliness or wholesomeness. When you subvert that visual identity by clipping them to your face and making them out of a material, which is, in this case, forged pattern-welded steel, it kind of re-codes that visual language to be one of conflict. It’s meant to evoke a sense of discomfort, and rather than [the clothespin] being a domestic item, it gets inverted and becomes more visceral and disquieting to see somebody in pain or discomfort in what’s maybe an internalized emotion in a classic male archetype.

How do the clothespins fit into the overall collection of items, such as the mask, the shackles, the pacifier?

A lot of the different items in that collection of pieces, they do follow that same motif of otherness, sort of masking an identity. So, a hood or a mask or something covers the face or obscures your facial features is obviously kind of a pop art or pop culture reference to the masked figure. And the masked figure could be a villain or a bandit or a robber, but it could also be a heroic figure. But, it’s also kind of a sense of loss of empowerment—loss of identity—when you obscure the face.

Do the materials used bear any significance?

I work primarily in forged metals, forged nonprecious metals, actually—namely, Damascus steel. It’s a kind of marbleized steel: Imagine you have two different colors of Play-Doh and you kneaded them together, folded, and rolled them out like you were going to cut cookies out of it. I do the same thing with steel, so those patterns are achieved when you etch them with an acid. And that material has a long history of being associated with these ideas of conflict and trauma, [because] it is historically used in weapons like swords and knives; it’s also been used historically to make shotgun barrels. It’s encoded with this idea of conflict.

On the woven side, you might have seen the pieces have this sort of knitted crocheted woven material—that’s actually Kevlar, which you probably heard of as an industrial textile material that’s usually used to make bulletproof vests and prosthetic limbs and cut-proof gloves for people who work in food service. So, it’s also this material with a context of conflict and trauma behind it. By combining these materials and making these wearable pieces, I tried to really push home that feeling of disquieting discomfort through conflict and sort of self-deprecating modeling of the pieces. They are unidealized. It’s not like a beauty shot, it’s not sexy jewelry—it’s much more on the conceptual side.

Where does your interest in jewelry come from and how did that lead you to the Academy?

I’ve kind of always grown up making things and working with my hands. I had a lot of family influence with other people who just loved to make things, and work on things, and do everything for themselves. With that background, I found myself engulfed in art as academia rather than a hobby or whatnot. So, I did my bachelors, my undergrad, [at] U.C. San Diego in visual arts studio, and there I did a lot of sculpture, performance art, and various other mixed media type things but still always making things.

I came back to graduate school after a few years of just how life happens, in terms of starting a family and buying a house and having a full-time job. The Academy gave me the option to still pursue my academic career one hundred percent remotely and online and still have a rewarding experience and come away from it with an accredited, terminal degree. So, that was a huge boon to my path there [and] was definitely the most positive thing about the Academy was the freedom to do things at my own pace and remotely, with a full-time job and a family and all that in parallel.

In what ways did the School of Jewelry & Metal Arts help you achieve your goals?

The [School of Jewelry & Metal Arts] just seemed like a great fit for the type of work that I was interested in making. Because I had done so much performance art, I was really interested in how the body and the form can interact with pieces and having the body as a creative medium of its own right. I feel like the department afforded me more freedom to pursue jewelry and metal arts in whatever way was most attractive to me. I came from a fabrication background of forging and welding, much more large scale and rather course forms of metalworking, which I then had to scale them into this super-refined, more intimate scale of the department.

What’s next for you?

With the degree wrapped up right now, I’m definitely just blasting my work out there in terms of applying for calls for entry, trying to build connections, build a network. I’m also trying to work more with local academic institutions—being a remote student has always been kind of a hurdle to get in-person gallery showings, because I’m at home making this stuff rather than at a school with dedicated showing spaces and out in the community. Having to forge my own path to build that network is a big challenge for me, so that’s definitely something I’m engaged in right now to get my work out there, get my name out there, and develop a better self-marketing plan for websites, social media. Ultimately, I would like to share some of these skills that I’ve accumulated over the years—from my bachelor’s to my master’s and my own independent study and personal interest in metals and fabrication.

What’s your advice for current Academy students?

I would urge any other Academy students who are embarking on challenging work—and when I say challenging work, I don’t mean technically difficult, I mean work that may not be popular in terms of its idea or concept or message—to fully take ownership over it and not back down on their ideas and ideals. That’s what art is—art shouldn’t be censored like that or people shouldn’t be discouraged in that sense. It’s really an open forum of communication, and I feel like that taking ownership is really important. Taking ownership of where you want to go and how you’re going to get there, and what you’re going to make, and what you’re going to say can be really intimidating. So, I would just urge them to not be afraid to take ownership over what they want to do.