Sculpture instructors and alumni are creating a street-level monument of famed social activist Norman Lear

The values of Academy of Art University are not simply rooted in fostering artists who make art, but in artists who make a statement. There may not be a better person who emulates that value than legendary television producer and social activist Norman Lear. So what better sculptors than instructors and alumni from the School of Fine Art – Sculpture at the Academy to create the first Lear monument of its kind in the country.

“We want our students to be artists who make statements. Not just artists who make pretty objects,” said Tom Durham, director of the School of Fine Art – Sculpture. “We want them to think about how you can say something about yourself, society and the times we live [in]. That’s what Norman did.”

For more than six months, Peter Schifrin, a sculpture instructor at the Academy, has been working as the lead artist, day in and day out, on the Lear monument—a colossal undertaking that will include a six-foot-three-inch bronze sculpture accompanied by a 10-foot bronze story wall.

This synergetic story began with Kevin Bright, the co-creator of the popular sitcom “Friends.” Bright sits on the board of directors at Emerson College in Boston where Lear graduated. With a dream to create a monument that captures what it feels like to be in Lear’s presence, Bright reached out to Schifrin, who had previously created a bust portrait of Lear back in the ‘80s that the TV producer was quite pleased with. Bright asked Schifrin to prepare some prototypes and see what he could do.

(L-R) School of Fine Art – Sculpture instructors David Duskin and Peter Schifrin and Producer/Director of “Friends” Kevin Bright with the six-foot clay prototype of their Norman Lear monument. Photo courtesy of Peter Schifrin.

“I was really excited,” said Schifrin. “I approached the Academy as soon as I got the email.”

He immediately knew the magnitude of the project would require the vision of a team and expertise in a variety of mediums and styles. He immediately reached out to Durham, fellow instructor David Duskin and alumna Darling Gonzalez to begin a collaborative journey.

“It’s not an individual’s vision, but a community’s vision that gets great work done,” explained Schifrin.

But for all those involved, including onlookers, the monument is in no way a statue.

“I hate the word statue,” Schifrin declared emphatically. “I prefer to use sculpture or monument. A statue to me is something dead, static and from the past.

“We wanted to make something inspirational that has a sense of future. Something that is aspirational and inventive.”

The need to create an innovative, inspirational monument spurred from Schifrin’s extensive knowledge of Lear’s history and the legacy he continues to mold. At 95 years old, Lear still makes headlines for his outspoken advocacy of social equality, the first amendment and arts and humanities. Just recently, Lear was asked to be a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors, but has boycotted the reception due to the host: President Donald Trump. It’s Trump’s budget proposal, which eliminates funding for the National Endowment for the Arts, that sparked his boycott.

However, it is Lear’s groundwork in the 1970s that revolutionized American television and, in turn, American culture. Before Lear made his mark, the programs that filled the living rooms of American families included “Leave it to Beaver” and “The Andy Griffith Show,” all white families who lived in ideal societies and whose biggest issues were the innocent mischief of its main characters.

Lear had a different vision for television. He created shows like “Maude,” “All in the Family” and “The Jeffersons,” one of the first sitcoms to feature a primarily black cast on primetime television. His characters discussed women’s rights, race relations and politics, subsequently shifting the dialogue of the American people.

“He was the first to introduce social issues in the storyline like no one else had done before,” said Durham. “He brought those concepts to the forefront in a very serious, but amusing way. He was honest with his audience.”

The artists working on the monument spoke about how their own values align with that of Lear’s and that their goal is to capture Lear’s impact on American culture, his character and humbleness.

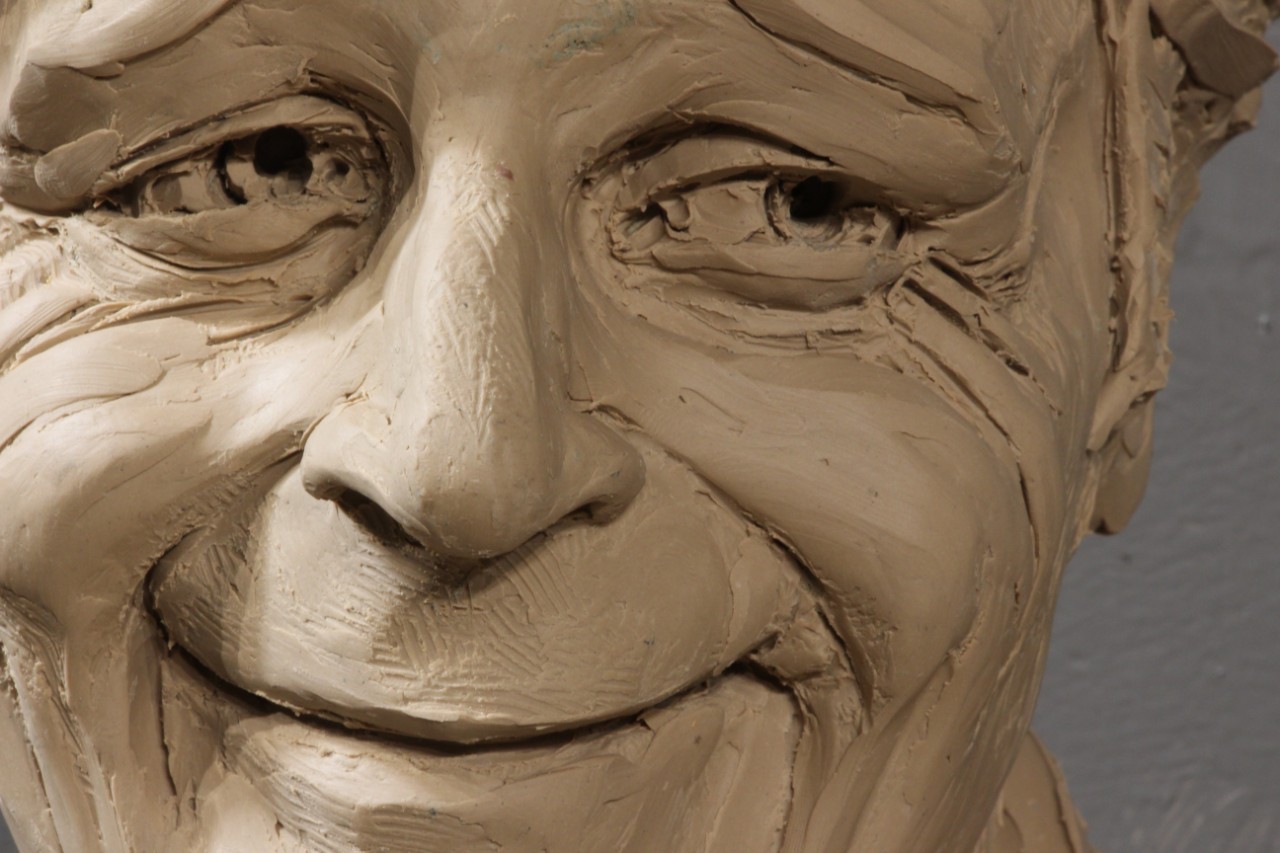

A close look at the clay prototype of the Norman Lear monument. Photo courtesy of Peter Schifrin.

Having spent hours at the Artworks Foundry facility in Richmond, California, the project has been a true collaboration. Schifrin was the primary artist for the figure, Duskin took lead on the story wall, Durham refined the figure, while also giving input, and Gonzalez helped with the graphics and presentation of the original drawings.

Since last spring, the team has come very far from those initial drawings.

There are three stages to this highly complex project: Design, fabrication and installation, the first of which is now complete. These months included countless drafts, cross-critiques among the artists and many variations of prototypes for both the figure and story wall.

Getting Lear’s expression, stance, age and persona just right was a great challenge, Schifrin shared. But in the end, the team got it just right. Last month, Bright flew from Los Angeles to Richmond to see the six-foot clay prototype of Lear in person. It was a rewarding moment for all involved.

Schifrin happily recalled the moment Bright walked up to the figure, looked at it for a long time, paused and finally gave his words of approval.

“His exact words were, ‘I feel like I am in Norman’s presence,’” said Schifrin. “That was the best thing I could have heard.”

Schifrin and Duskin work together while forging hot steel for the project. Photo courtesy of Peter Schifrin.

Another important aspect in creating a monument that not only communicated Lear’s presence, but also his message, was by constructing a place, not just a figure, something Duskin referred to as “place making.” The story wall was imperative for creating such an experience. The figure will lean against the wall engraved with text of Lear’s story and quotes from some of his most famous shows, including “Maude,” “Good Times,” “All in the Family” and “The Jeffersons.”

“We wanted visitors to come to a place and be inspired to look more deeply into Norman’s legacy,” Duskin said. “Norman was an innovator. If we’re going to have a tribute piece, it has to be innovative and move beyond the typical way people do monuments.”

Duskin talked about how the monument steers away from the classic statues normally seen in Boston, like that of George Washington or John F. Kennedy, which tower above the observer in an almost intimidating way.

“The figure will be on street level so you can go right up to him and look him in the eye. He won’t be perceived as being greater or better than you, but just another version of you, like Norman says,” explained Duskin.

The next step for the clay sculpture is being cast in bronze, a multi-step process, while the story wall is sandblasted with engravings. The unveiling is scheduled for May of 2018, where people will be able to experience Lear’s “just another version of you” presence themselves. Until then, the artists will be hard at work.

Featured photo: Schifrin works on getting Lear’s expression just right for the monument. Photo courtesy of Peter Schifrin.