The industry veteran explained the pivotal role maquettes play in developing and refining animated characters

By Cristina Schreil

In 2000, Andrea Blasich was in Los Angeles, riding in the back of a car. Wedged between film producers and directors, he cradled a maquette sculpture of a fish named Oscar. Their objective: pitch it to Will Smith, in the hopes he would voice him.

For Blasich, witnessing Smith meet Oscar was impactful. “That was really gratifying to me to be there, to see his expressions,” he said by phone. “They can see the character they’re going to embody.”

Clearly, Smith said yes—and starred in the DreamWorks animated feature “Shark Tale.”

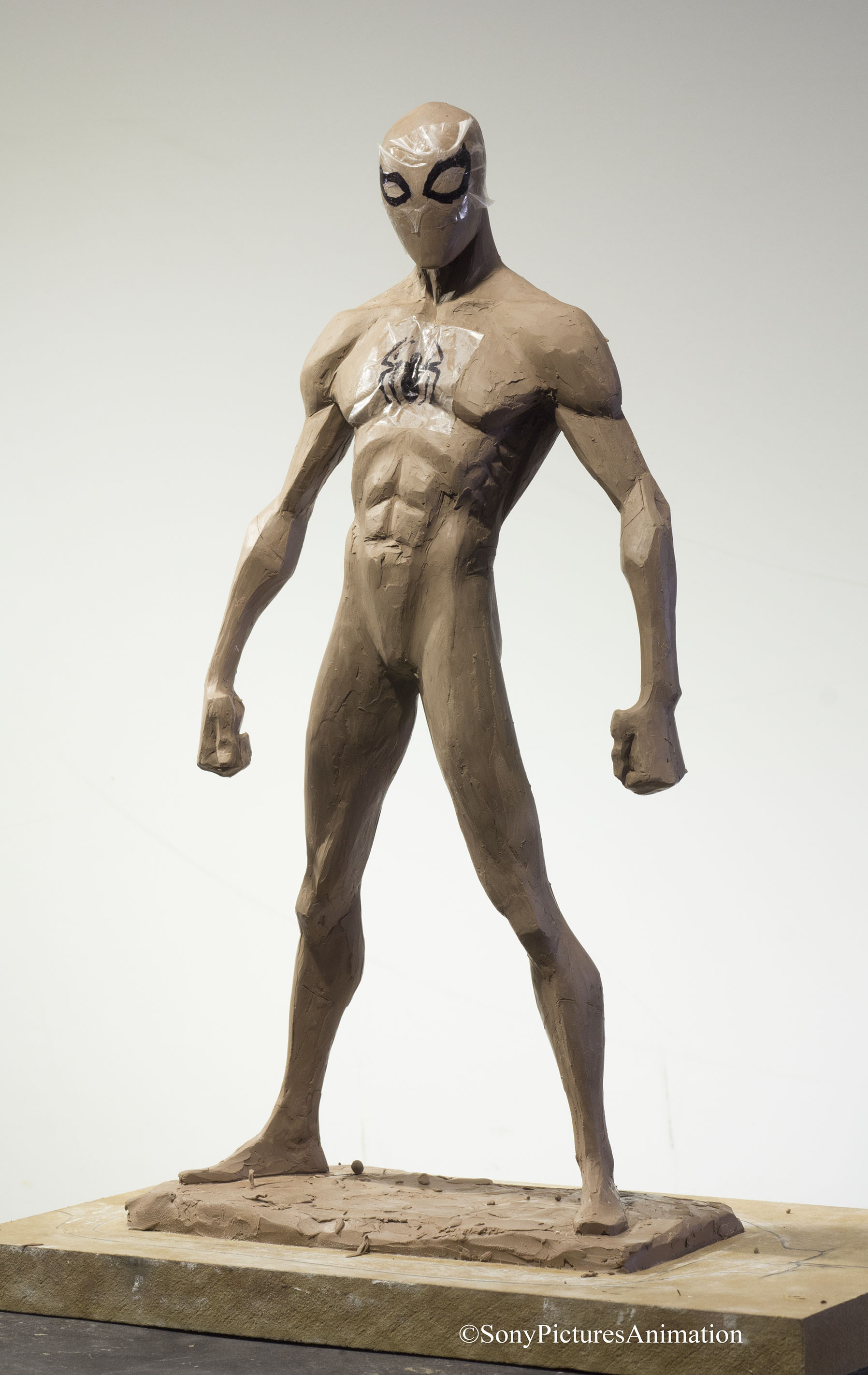

The original maquette Blasich created for a character in “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.” Courtesy of Andrea Blasich.

Blasich, Academy of Art University instructor in the School of Animation and Visual Effects (ANM), has been a maquette sculpture artist for nearly 30 years. As his “Shark Tale” anecdote attests, maquettes can translate a film’s concept. However, he mainly provides a pivotal part of the character-development process on animated films and video games, helping establish and refine characters’ look and feel. To explain further, he recalls early Disney films. “A maquette was used for animators and directors to visualize character design that they came up with on paper in a three-dimensional way,” Blasich said. Often, the maquette artist jumps in after the initial character concept. From there, it’s a back-and-forth development. “The beauty of this medium is that you can see [a new version] right away,” Blasich said. “Especially the director can touch the sculpture, can work with you on it, and can gain ownership.” He works with oil-based clay, a faster medium that lets him manifest new ideas in the heat of the moment.

Maquettes also assist animators. “The animator can take the sculpture and use it for really difficult angles, like an upshot or downshot, or showing three-quarters of the face, especially when we’re doing realistic characters,” Blasich explained.

Blasich, born, raised and trained in Milan, Italy, credits classical masters like Michelangelo, Bernini, Troubetzkoy, and Bugatti as inspirations. Maquettes, he’s quick to remind, have been vital to sculpting for centuries—in making scale-model rough drafts of larger commissions. In Italian, “maquette” means “sketch.”

Upon moving to the United States, he worked for DreamWorks, Pixar, Blue Sky Studios, WarnerBros., Sony, Lucasfilm, and Tonko House. Since creating maquettes of the main characters for his first film project, “Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas,” he’s worked on such films as “Brave” and “Ice Age: The Meltdown.”

He said for “Sinbad,” where the characters were more anthropomorphic and graphic in style, it was tough for a supervising animator to understand their look without his maquettes to clarify.

Blasich’s latest credit is the Oscar-winning “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.” There, he helped design Peter Parker, Gwanda and Green Goblin. “I was more involved in the character design,” he said, adding it was a positive, friendly experience. “It was a pretty collaborative process, pretty organic.” Over the years working on different projects, however, it’s not always so straightforward. “Sometimes it’s frustrating when you can’t get the vision of the director, you don’t know what they want, or maybe they don’t know yet,” he said. “So, you have to play around until you find that crack. And then you can go through and find a solution.”

Blasich’s career also saw the transition from 2-D animated films to CG. “Shark Tale” was the first to scan one of his maquettes to create the CG image. “It was an interesting process to see how what you sculpted would materialize in CG form,” Blasich said. “In Spider-Man, I was really impressed by the way they kept the CG really close to the sculpture,” he said.

Blasich leads Academy students in maquette creation. Courtesy of the School of Animation & Visual Effects.

In Fall 2018, Blasich taught his first ANM class, on designing clay maquettes for feature films and games.

Jessica Galvan, a B.F.A. stop-motion animation fabrication major, was one of Blasich’s students. “Each sculpture that Andrea had us create taught us different ways of interpreting the concept,” she wrote in an email. “I learned that there is a lot of problem-solving to be done before going in and sculpting.” She added that working alongside students with different approaches and styles was rewarding. “The atmosphere of the class was engaging.”

Fellow classmate Caroline Ford, a student in the School of Fine Art, also found the experience interesting. “Learning to copy and render forms from a 2-D picture was kind of like a brain exercise. It made me see things a little differently,” she reflected. “It was really a privilege to be able to learn from someone so well known in his field.”