By Greta Chiocchetti

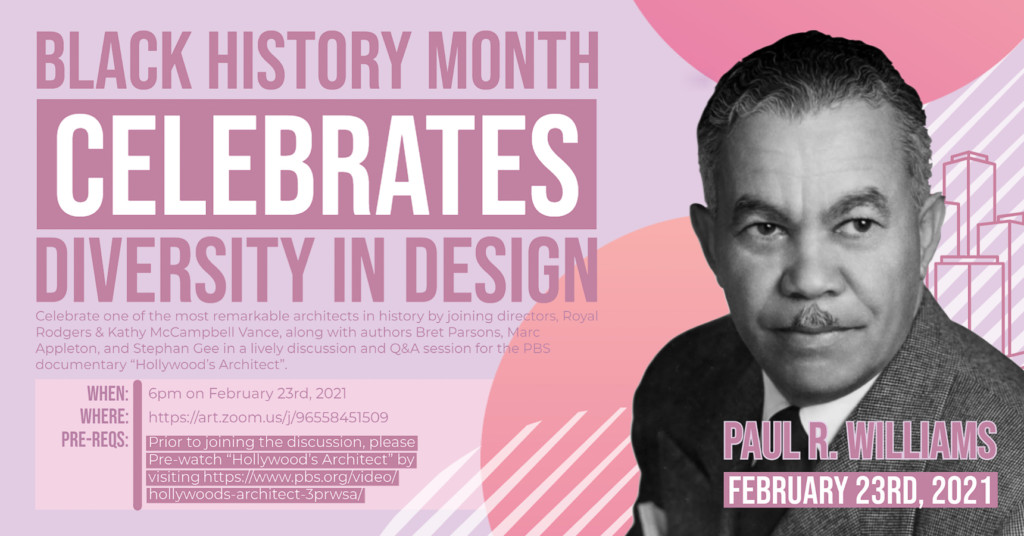

In honor of Black History Month, the Academy’s School of Interior Architecture & Design (IAD) hosted a live webinar on February 23 to celebrate the life and art of Paul R. Williams, the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects and a prolific designer who left his mark on Southern California.

IAD faculty discussed Williams’ legacy with co-producers/directors of a new PBS documentary, “Hollywood’s Architect: Paul R. Williams,” Royal Rodgers and Kathy McCampbell Vance, along with Bret Parsons, Marc Appleton, and Stephan Gee, the authors of “Master Architects of Southern California 1920–1940: Paul R. Williams.”

“All I can say about Paul Williams is he is a God,” said Parsons. “He’s probably one of Los Angeles’ greatest architects. Just an extraordinary man in every way. Still to this day, his projects are revered—no pun intended, his middle name being Revere.”

Also known as “Hollywood’s Architect,” Williams designed over 3,000 homes and commercial buildings, many in neighborhoods he wasn’t allowed to live in at the time, during his prolific career between the 1930s and ’60s. Famously, Williams learned to draw upside down to work across the table from clients who didn’t want to sit next to a Black man. Despite the societal constraints around him, Williams designed some of the most beautiful—and expensive—projects in the U.S., including those for Lucille Ball, Cary Grant, and Tyrone Power.

Moderated by IAD Vice President of Branding Kay Evans, the webinar kicked off with a presentation by Parsons, Appleton, and Gee. They spoke about Williams’ influence in shaping the architecture of Southern California during the boom years between World War I and World War II—despite not being welcomed into many of the communities he would later beautify.

“We often talk about Williams not being able to live in the neighborhoods or the houses that he designed. Well, what does that actually mean in practical terms?” said Gee. “It means that the contract included a clause that said, quite literally, ‘Property shall not, at any time, be lived upon by any person whose blood is not entirely that of the Caucasian race.’”

Williams’ design pushed the boundaries of the expected, Gee explained. At the time, much of the emphasis of a home’s layout was in the front, with the backyard being an afterthought. Williams shifted the focus to the back of the house, creating a layout that could overlook a manicured backyard.

“Williams knew that most of life in the house happens at the back of the house, where the kitchen, dining room, and lounge is,” said Gee. “This design is important because it gets Williams an awful amount of attention.”

The authors, who wrote about Williams as a part of a larger 12-volume series exploring prominent architects of the era, revealed that many of the most prolific designers of the day—including Williams—have been left out of today’s discourse.

“Some of these architects have been largely forgotten. There were few or no books on them. And part of the reason for us deciding to publish this series was to remind people that this work was really special. These architects were special,” said Appleton. “With the things happening—the loss of a lot of these houses [to demolition]—we really needed to be mindful of and caretake [their legacies].”

In the Q&A portion of the evening, Rodgers and McCampbell Vance shared about the behind-the-scenes making of the documentary, highlighting the importance of telling a genuine story about Williams’ experience as an African American in a society that aimed to constrain him.

“Our goal was to make sure we were true to his story, from the point of view of somebody who might have experienced similar difficulties, similar boundaries that were put in place at the time,” said McCampbell Vance. “An aspect of his personality that I think propelled him was his grace. I wonder if his childhood being the only Black kid in a white school somehow prepared him to operate in this white world all these years later.”

Evans asked the filmmakers if Williams knew what an impact he was having on the industry and the Black community.

“He definitely knew the impact that he had on his own community at that time. He and his wife were right in the heart of the African American community of L.A., through their church and through their social connections, and through all the things that he did for the community,” said Rodgers. “But I don’t think he ever could have dreamed of the impact that he has today.”

“There are many, many, many other Black heroes and leaders who have built this country. He’s just one of them,” said McCampbell Vance. “We want people to know that Black people have a history. Americans have a history that includes Black people, and everybody needs to be aware of that.”

Watch the event in full below.