By Nina Tabios

Stephanie Thomas’s philosophy as a disability stylist centers around three key principles: accessibility, safety, and fashion. In her line of work, styling is “co-creating.”

“Is it easy to take on and off? Is it medically safe?” Thomas said, citing the Disability Fashion Styling System she formed in 2004. “That means it’s good for the person’s body type, their lifestyle, and it also has to be something they absolutely love.”

But the goal is to one day eradicate the need for stylists and activists like herself. Thomas has dedicated almost three decades to empowering and educating people with disabilities through fashion, both as a stylist and as the founder of Cur8able, a disability fashion lifestyle website.

As a congenital amputee, Thomas has personally experienced difficulties with dressing as well as the lack of visibility in fashion for people with disabilities. However, in recent years, it seems like her efforts are starting to pay off. In 2019, Thomas was highlighted in publications such as The Guardian, Vox, People, and Paper, and was named to the Business of Fashion 500, which identifies individuals shaping the industry. A year prior, Tommy Hilfiger and Target introduced their adaptive clothing lines.

“I want there to be a day where there is no need for disability fashion stylists,” said Thomas, a 2013 M.F.A. fashion journalism graduate and 2018 Distinguished Alumni Award recipient from the Academy of Art University School of Fashion. “And that’s because all stylists are now disability fashion stylists. They understand body types with disabilities, there is clothing design for disabilities. I want to put myself and this part of my work out of business.”

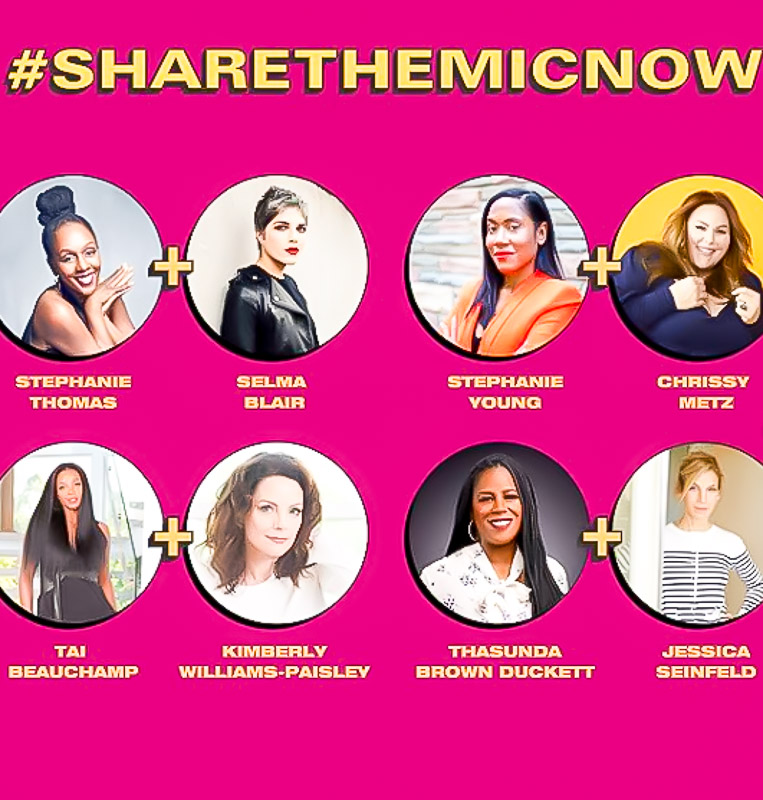

Thomas believes the work she does is intersectional. Recently, she participated in the #ShareTheMicNow campaign, where 50 Black female activists, celebrities, and entrepreneurs took over the Instagram handles of A-list celebrity white women. Taking over actress Selma Blair’s Instagram, Thomas was among notable Black women such as Angelica Ross, Elaine Welteroth, Lindsay Peoples Wagner, Rachel Cargle, and Yvette Noel-Schure.

“As a Black woman with a disability,” Thomas said during the live takeover on June 10, “I have a story to tell that you pretty much can’t see.”

Art U News caught up with the Los Angeles-based stylist and activist to talk about how her work has shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement, and how art and using your voice can be advocacy during these decisive times.

How were you approached to take part in the #ShareTheMicNow campaign?

It was [journalist and Vox political correspondent] Liz Plank. I used to see her on MSNBC as a correspondent and when she interviewed me a year ago, I got something from her one day and she’s like, “You are a badass and I would love to interview you.” And I was like, “Okay when someone starts out like that, let me check her out!”

She wrote this really fantastic book on what it means to be masculine and just male fragility, their ability to navigate masculinity, and the difference between toxic masculinity [and male fragility]. It’s a great book—well researched—so we kind of became fast associates and have become friends over time. [For #ShareTheMicNow], all she did was reach out [to] me like, “Steph, I’m doing this big project, are you in?” If it’s her, I’m just like, “Yup, I’m in.” I didn’t even know what I was signing up for.

In what ways can opportunities like this make an impact for you?

#ShareTheMicNow changed my life in that it’s gotten me a few thousand more followers, which is great because hopefully, people will spread the news about dressing with disabilities. But it’s also given me the courage to start creating, to actually take Cur8able to where I’m going to be putting on and creating COVID-friendly productions, six-series productions with my Cur8tors first and then with other people. I spend a lot of time bringing other people’s visions to life, but I want to bring to life my own vision of what I’m not seeing out here.

Has COVID-19 affected your work as a stylist?

In COVID-19, I had to put together a document that I will be giving out to all of my personal styling clients and to all of the productions I work with. I require social distancing but if I’m in an environment where we’re not socially distanced, we need to have masks. That’s been a major change because it’s me having to say, “I take this pandemic seriously and anyone that’s going to work with me, no matter what their personal views are, they’re going to have to wear the mask.” And that’s because I would be putting my own life in jeopardy. Even if we don’t agree on what the pandemic is, there’s a certain thing as professional decorum and if you don’t think enough of me to respect my perspective as I’m respecting yours, then we can’t roll. It’s just that simple.

When you’re not on set, you are also an active advocate for people with disabilities through your Cur8able website. How has that sector of your career been influenced by the pandemic?

I actually had the opportunity to kind of leapfrog some of my goals and get right to what I’ve been wanting to do for a few years now, which is create content at the intersection of fashion and disability. I’ve been able to pivot my Cur8able website and turn that more into a place about community, things I curate, and current events. It’s very straightforward, very easy to understand; my shopping sliders are split into seated body types, standing body types, various body types, and I just want to make it a resource for people but make it personal. It’s pointed, but it’s also not me trying to be a news outlet. It’s me telling you what I’m thinking, a true blog.

But before, the first opportunity COVID-19 provided was for me to slow down and to really focus on my own values and to focus on really mastering the idea of not being able to change others but definitely living according to my own worldview. Because [there are] so many opinions about what’s going on, people talking about it’s a “plan-demic,” whereas I see it very much as a pandemic. I’m very conscious, I stay safe and I would really stress out in the beginning because people weren’t being so safe and didn’t seem to be taking it so seriously. I would say I’ve been giving the gift of learning to live by my worldview and [to] accept others’ worldviews that are different from mine.

During your #ShareTheMicNow talk, you mentioned that there are similarities between disability rights and Black rights. A lot of your work is intersectional—in what ways has the current Black Lives Matter movement made an impact on you?

Black Lives Matter has shifted my life and my mind forever, for the rest of my time on Earth. And I say that—and this is not hyperbole—but one of the things that I did not realize was that I was living according to white supremacy thoughts and ideas of who I am. Every time I looked in the mirror and wished my hair was a tad bit straighter so it would be easier to manage, or every time I would look at my hair and I would just feel like, “Ugh,” or someone would comment on it, like, “Can I touch it?” Those microaggressions really were creating a wall to me loving myself. And I feel like this time has given me the gift of being able to look at things, hear these little comments in my head and separate myself from them and embrace myself completely and wholly without hating someone else. The one thing I will not do is give someone who hates me extra power over my life.

And yes, it is intersectional. I can never not do it. Me being me is advocacy! But here’s the beauty of it: you being you is also advocacy. Everyone has a voice and that’s really the exciting, beautiful part of being who we are. My family never treated me like I had a disability—and there is nothing wrong if they did—but I never grew up hearing any whack, apologetic language like “special needs” or there was never this apologetic tone or this idea of, “Let’s coddle her.” My brother always said, “Don’t be the victim, you’re not a victim.” And so, I was always treated in a way that encouraged me to use my voice.

What is your advice for students who want to use their voice, and their art, as advocacy?

You’ve got to know the “why” behind the “what.” The “why” behind the “what” will indicate the path. My “why” is always destroying negative perceptions of people with disabilities. I knew I was a storyteller and so, fashion styling is a form of storytelling. And I can tell you, it’s evolved over the years for me. It took me years to figure out how to tell this story in a way that would really resonate with the zeitgeist of the time. A lot of people that were doing the same work I’m doing 20 years ago write me today and say, “Oh my gosh, you kept going.” I was like, “What else am I going to do? The problem isn’t solved!” So, that’s the last thing: keep going. Even if you don’t know what to do, let the “why” motivate your movement. And don’t think you need to have it all figured out to keep going.

And for people who want to help the movement, my advice is to learn about groups you’re unfamiliar with by interacting with them. I learned a lot about people by going straight to the source—I prefer going out, talking to people, and watching interviews. My goal for my work is for there to be no need for my work one day. I don’t want to have to convince people that my life—and lives of people like me—has value; I want equity, I want access. I need us to get to a point in society where you can actually look at me and see me and understand that I’m not valuable because of degrees or work, I’m intrinsically valuable because I’m here.

How do you take care of yourself during these unprecedented times?

I think a lot of healing is happening. And the way I escape is “Hamilton” the musical, “In the Heights” by Lin-Manuel [Miranda]. Music helps me to escape, and I’ve been watching any and everything, listening to a ton of audiobooks. I did start exercising again which makes me feel so much better mentally. I just go downstairs super early in the morning when no one’s up because I get up at 4 a.m.

But, to be honest, at first, I didn’t take care of myself. The more attention I got, the more I wanted to shrink. So, I would just do things that were against my own better health. I had so much to do—my entire website, learning WordPress, a relaunch, [to] put up new posts. I did all of that by the end of May, then June happened and I just shut down. With the Black Lives Matter movement, all of a sudden everyone wants to be an ally and, at some point, I couldn’t take it. I live this. It’s new to you and, for some people, it’s a novelty but this is my existence in the world. So, it was tough for me to talk about it and to have things talked about in the news, in the zeitgeist, on the internet that you live all your life.

I just have to say, I’m okay with not being okay, but it was a struggle. There were some days just sitting and crying, some days not even understanding what I’m feeling like. But as an entrepreneur that has an opportunity to work, I have to do the things that are going to help me be able to take care of myself. The goal is to get someone to invest in me and what I’m doing and, from there, be able to hire other people with or without disabilities that are interested in this space, really help them hone their voice, mentor them, and send them out in the world to impact it.