By Isabella Cook

Every journey worth taking begins with a leap of faith—this is especially true in the case of David Dibble, an Academy of Art University alum with a successful artistic career as a gallery landscape artist, an animation studio color artist, and an art instructor.

Dibble’s interest in art began early in his life, and he credits his formative years as having greatly informed the work he would create later in his career. His childhood home in Utah, a generational farm established in the 1880s, imparted a deep appreciation not only of nature but of man’s ability to harmoniously impact the corner of the world they occupy.

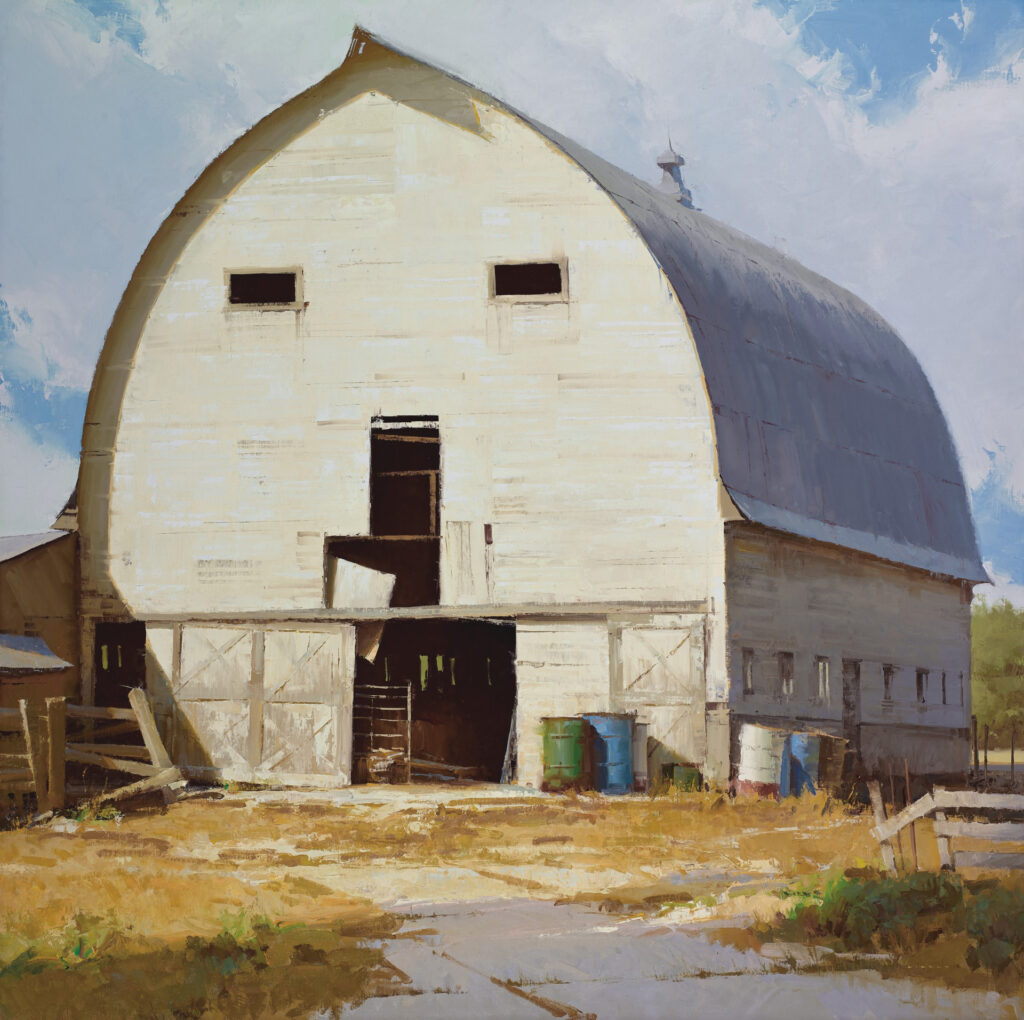

“It’s no surprise where my artistic leaning lies; it is very much rooted in nature and the landscape but with an order and a structure I think is really fascinating,” Dibble explained. “[My work] typically doesn’t try to eliminate man’s interactions with the landscape, but rather to show the struggle between the two, particularly in agricultural settings.”

After graduating from high school, Dibble served as a missionary in Brazil before traveling to Italy to study art. Upon returning home, Dibble attended Brigham Young University (BYU) and earned his B.F.A. in illustration. Though he was already a talented artist by this point, Dibble knew that he needed to further hone his skills if he wanted to succeed as a professional painter.

“I graduated and did freelance for a year only to realize I wasn’t professionally where I needed to be,” explained Dibble. “Prior to that time, I hated oil paint because it felt messy and uncontrollable. Looking around at museums, I realized that if I was going to say the things I wanted to say, the big ideas I had about life and nature, I needed to be an oil painter. And for that, I needed more training, so I went to the Academy of Art specifically to study with William Maughan and the other amazing [instructors] there.”

Dibble graduated from the Academy in 2008 with his M.F.A. and enough new skills to launch deeper into a fine art career. Early in his time at the Academy prior to taking Maughan’s landscape class, Dibble fondly recalls standing outside of Maughan’s landscape classes “like little boys in the early days of baseball, looking through cracks in the fence and hoping to catch a glimpse.”

“His thesis work was ambitious, requiring him to fabricate large panels for attaching to the exterior of a large structure,” recalled Maughn, who describes his former student as “an honest and generous man.” “I have found him to be ambitious in many projects, including building his own elaborate easel.”

The Academy alum shared that his other instructors were equally inspiring, and the late Ruben DeAnda was also a cherished mentor.

He also took great joy and a lifelong passion from the Academy’s plein air landscape lessons, despite his romantic notions of painting outside with his French easel being quickly drowned out on day one by the San Francisco rain.

“It just started raining and raining, and I was having to dump out my easel,” said Dibble. “I came home dripping like a wet cat and utterly defeated and thought, ‘This is really hard.’ So, therein began the long journey of learning to paint landscape, as I realized that loving nature and having the skills to depict nature visually are separate things.”

While at the Academy, Dibble married his wife, Liz, and moved back to Utah to complete his thesis: a mural painted on his own family farm. This project was one he had planned at the beginning of his studies at the Academy, a goal that gave him a focus and purpose in his work.

“I can fully and firmly say the Academy was a huge part of my success and journey, and I still remember standing on the Montgomery Street sidewalk with the financial aid papers in my hands,” said Dibble. “The risk-averse part of me still had one foot out the door, but that was the moment where I really jumped in with both feet and said, ‘Yes, I do believe in myself.’”

Dibble’s willingness to see the wisdom in investing in himself and his artistic education is a large part of how he turned a passion into a profession. Now, Dibble is an established world-class oil landscape painter known for his gallery paintings—primarily of agricultural structures. And though capturing the essence of rural-urban landscapes through oil and canvas is his passion, Dibble has also worked his magic in animation as a color artist for 20th Century Fox’s Blue Sky Animation Studios. He created concept art for films, including “Rio,” “Ice Age 4,” and “Peanuts.”

“‘Rio’ was probably my favorite animated project,” said Dibble. “It was my first film, and that’s a big part of why it was so magical for me, especially since it was dealing with Brazil, where I’d lived for two years.”

“As a color artist in the industry, you really need to have the skills of a fine art painter,” Dibble continued. “That I got to experience animation in this fine art realm was really exciting, especially when you can see your work come to life on screen.”

He eventually left the film industry to become an associate professor of illustration at BYU. Dibble departed his role at the university after six years to pursue, at last, full-time professional painting. The landscape artist may have started out his journey as a young man who wanted to draw, but by honing his skills, working hard, and believing in himself enough to make that initial investment in a fine arts education, his leap of faith led to soaring success.

Dibble’s advice for current and aspiring artists alike is to say goodbye to perfectionist tendencies and fear and to find some purpose in painting.

“Let go of perfectionism,” advised Dibble. “I think I could have done much better to let go of fear early on. Even though I was trying consciously to not make decisions based on fear, it took time to do. I think a lot of artists seek validation through art rather than seeing art as a vehicle for communication and service to others. Often, when we’re young, we make art because we’re told we’re good at it, so we continue to seek that approval. It may be fine to start that way, but that motivation becomes increasingly problematic over time and leads to a fear of making mistakes and taking risks because they may jeopardize that approval. Creating for the right reasons and seeing mistakes as part of the process is crucial. Because in the end, who we are becoming and helping others to become is the real power of art.”