By Isabella Cook

This past fall’s American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) Conference, held at the Moscone Center in San Francisco November 11–14, featured a guest lecture by esteemed Academy of Art University alumnus Eric Arneson.

Arneson, who graduated with a B.F.A. from the School of Landscape Architecture (LAN) in 2016, is a design partner at Topophyla Landscape Design, based in Santa Barbara, California. Fellow Academy alumna Nahal Sohbati is also a design partner at Topophyla.

“The part of the Academy that I love is that there’s a lot of freedom to explore whatever interests you want. That’s how I got into the drone element of landscape architecture,” Arneson told Art U News in a post-conference interview. “The last year I was at the Academy, they had a course for drones in film and photography, and when I took the course, the teacher let me explore my interests independently. I found this new technology and thought it would be a great tool to incorporate into our workflow and projects. It was incredibly helpful, grounds you in reality, and helps you find the cutting edge of the profession.”

Arneson opened his ASLA presentation by discussing the earliest forms of aerial photography and mapping, from hot air balloons to airplanes. The application of these early inventions, he explained, opened the door to a novel way of viewing the world.

“A really great example of early aerial photography is this photo of aerial damage of the 1906 earthquake,” said Arneson, discussing a displayed image. “This not only was a means of portraying mass destruction but was also a means of assessing and documenting the damage. Aerial photography since then has progressed significantly.”

Arneson further explained that aerial photography has only recently been “democratized” due to the creation and distribution of drones, which effectively removes the need for specialized skill sets, such as that of pilots, in aerial mapping and photography.

With the early origins and uses of aerial mapping and photography established, Arneson turned his attention toward the present and future by addressing a basic but necessary question to lay the groundwork for the rest of his lecture.

“What is a drone?” Arneson asked the audience, referring to a photo behind him of a flying robot that may move either autonomously or by remote control. “A drone is a really broad-term definition for a wide array of machines, from small children’s toys that can fit in your hand to military-grade machines. What we’re dealing with today is in the middle.”

According to Arneson, there are two categories of established drone use: qualitative (artistic) and quantitative (data-driven). The qualitative use of drones includes fields such as cinematography, photography, and real estate while the quantitative use of drones falls under the categories of STEM fields including, but not limited to, construction, engineering, and research.

Landscape architecture, Arneson asserted, stands in the middle ground of these categories, equally utilizing the artistic and scientific applications of drones, aerial photography, and mapping to gather more accurate details, images, and data about prospective plots of land. This use of drones is a relatively new and integral tool for landscape architects, one which paves the way for more informed outdoor designs that help professionals to work with the surrounding environment rather than against it.

Before delving further into drone-aided design tools in landscape architecture, Arneson clarified that the drone strategies and techniques he would be discussing are not to replace professionals (such as licensed site surveyors). Instead, drones should be used as additional tools, the purpose of which is to augment and assist in the process of landscape architecture.

The first tool of drone-aided design conveyed by Arneson is video site tours, including 360-degree site tours. This function allows sites to be seen from every angle, including aerial and is excellent for remotely viewing a site and recording it for later reference. Drones can also provide high-resolution imagery.

“Along with accurate rendering, we have breathtaking video, which is an amazing tool,” said Arneson. “One way we can use this video is as a virtual sight tour, which could theoretically be live-streamed on a Zoom call in real-time. 360-degree panoramic photos are a fantastic tool because you can get very high-resolution photos and you can zoom in and capture everything. These can also be used in virtual reality.”

Next, Arneson turned his lecture to drone mapping, a topic that includes a wide array of design tools drones provide to the field of landscape architecture. Photogrammetry, the art and science of using multiple overlapping photos to create a 3-D digitally-rendered model, allows landscape architects access to accurate digital renditions of sites.

“Photogrammetry is essentially how your two eyes function,” explained Arneson. “You have a left and a right eye, and each [projects an image] to your brain. The same can be said for drones.”

Arneson shared that these tools ultimately make it possible to create a digital twin of a site, allowing landscape architects to analyze volumetrics and area takeoffs and create 3-D printed models of sites.

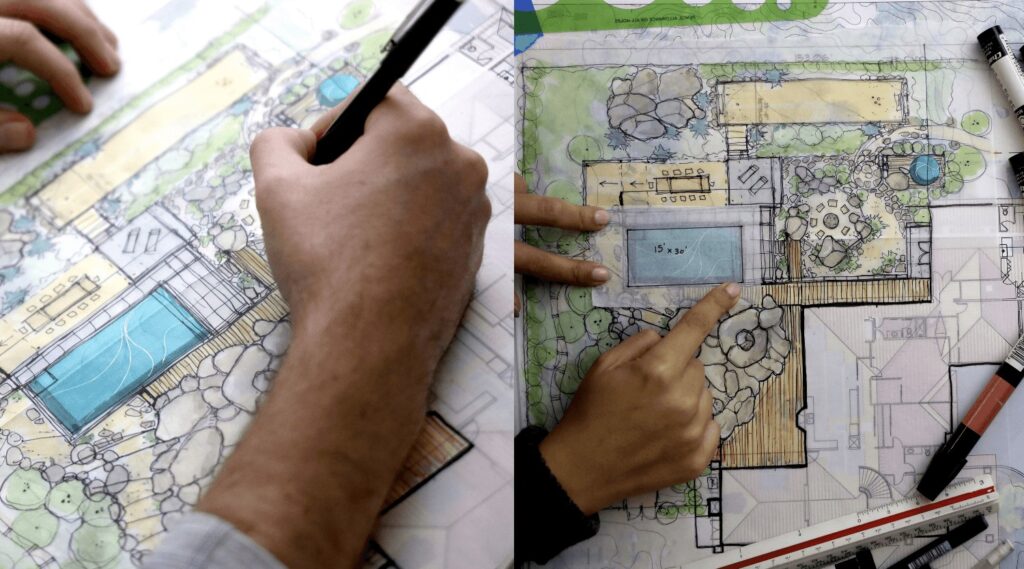

“Essentially, with all of this data, we are able to create a digital twin of this site—a kind of a virtual site analysis tool that we can always refer back to,” said Arneson. “We worked on a house, used drones to scan boulders and such … and used the 3-D software to create a 3-D rendering. Because of this, they were able to move forward in the design process confidently and were able to create a design that was sensitive to the existing conditions. This is an example of orthomosaic mapping and 3-D modeling to create a 3-D rending.”

Using three sample projects in San Marcos, Vista, and Petaluma, Arneson demonstrated to the audience how he utilized these various drone-aided design techniques in real-life landscape design scenarios. He discussed being able to accurately document a boulder-filled backyard and using the readings to integrate the landscape design around them to isolate pre-existing structures and use their placements to predict views. For Arneson, drones bring a whole new world of possibilities to the field of landscape architecture.

“We’re barely scratching the surface [of drone-aided design], and it’s exciting since it’s an entirely new technology,” said Arneson. “The future applications are way beyond what I can even imagine, and it’s exciting because every year, there’s a new drone, feature, or software. It’s constantly evolving, and it’s going to keep changing forever. Our duty, as designers, is to stay up-to-date with these technologies.”

“We teach our students to dream and to make those dreams a reality,” said LAN Director Heather Clendenin. “Landscape architecture is a really complex profession, and you need to know a lot about a lot. Eric is a conduit for landscape architecture. We’re all just extraordinarily proud of him and that he was selected to speak at the ASLA conference—he saw the writing on the wall with drones, and he pursued it. He’s one of those people that when he says something, you listen.”