By Greta Chiocchetti

What if solutions to the Bay Area’s homelessness crisis could be housed in a thoughtfully-conceived, user-friendly smartphone application?

Last semester, students of the School of Architecture (ARH) at Academy of Art University partnered with faculty and students from University of California Hastings College of the Law, along with creatives and developers, with that end goal in mind. As part of the Hacking Homelessness Design Challenge, a hackathon in which participants were asked to devise tech-forward solutions for the many facets of the homelessness crisis, ARH students lent their design skills to conceptualize a path to a better future for the city of San Francisco—and its 8,000-plus unhoused residents.

Working over the course of a week, the students developed and presented their solutions, blending the law students’ policy knowledge with developers’ tech-savvy and ARH students’ design chops. By the end, the teams had created innovative, user-friendly ways to tackle problems ranging from eviction to lack of low-income housing developments to lost property as a result of homeless sweeps.

“One profession doesn’t have all of the answers,” said Charles Green, ARH instructor and founder of the Berkeley-based architecture firm Atelier Siletz. Green participated in the design challenge himself two years ago. “I think the more that we can collaborate with other professions, the better chance of solving these large social and urban issues.”

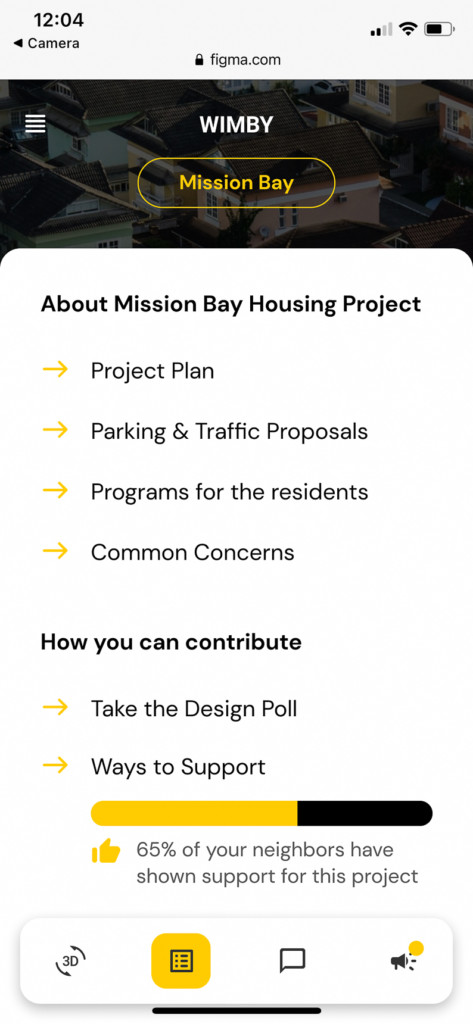

Online B.Arch student Brett Greene lent his creative expertise to the hackathon’s winning presentation: “From NIMBY to YIMBY.” NIMBY, an acronym for the phrase “not in my back yard,” is a characterization of residents who oppose proposed developments in their neighborhoods, preventing affordable housing projects from moving forward. Greene’s team developed an app that focuses on helping NIMBYs visualize what these projects would look like, making them less likely to shut them down in the initial stages of planning. His team’s application was unique in that it wasn’t designed for those experiencing homelessness to use, but rather for communities with a lot of power—with the goal of making housing projects less intimidating.

“I think that’s a big barrier for a lot of people—that they can’t really visualize things unless they can almost experience it,” said Greene, whose B.Arch thesis focused on the issue of homelessness in his hometown of Nashville. “At heart, we all are NIMBYs in some way, which I found out from sitting down at the dinner table with my wife and my kids. I started proposing scenarios, like what if I was going to build a multi-family affordable housing complex? What would be your concerns? By understanding that people just naturally are afraid of what they don’t know or are not informed about, that kind of allowed us to understand why everybody is a NIMBY. So really all we need to do is inform the public or inform the neighbors of what we’re doing and get them involved, so they can come on board and not be those who are standing in the way, just out of fear for the unknown.”

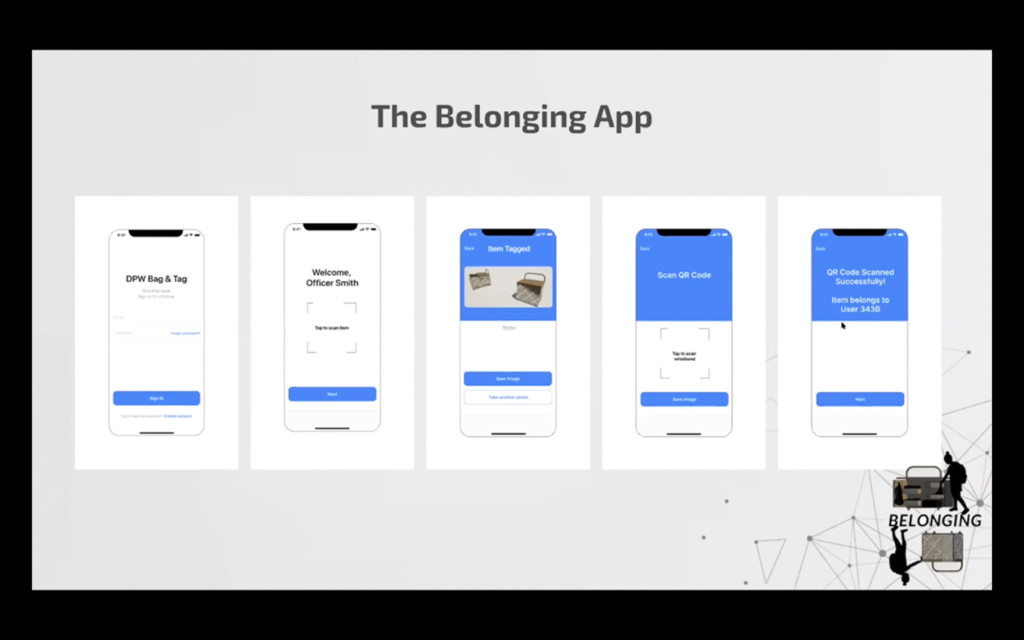

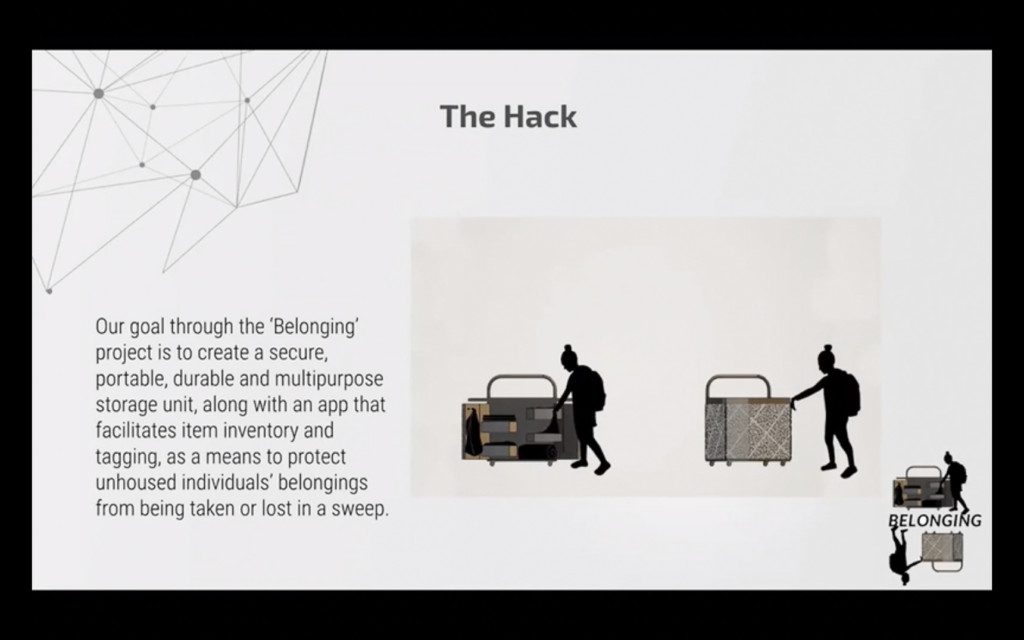

Kyle Lanzer, Iveta Posledni, Anahi Servin Pacua, and Connor Bowes also represented ARH in the hackathon with their inventive designs for a solution to the pervasive issue of stolen property while living on the streets. Department of Public Works sweeps often result in property being taken, tagged, and relocated to warehouses where bureaucratic systems can make it nearly impossible for those experiencing homelessness to retrieve their belongings. The team’s solution? Sleek, functional, mobile carts with built-in storage compartments that can be affixed to a QR code in the event of property loss—making it much easier to track and return.

For the designers on board, it was a valuable exercise in cross-collaboration.

“We as architects get kind of hyper-focused in our own world of architecture,” said Green. “I think the Hacking Homelessness event with UC Hastings was an interesting opportunity for students to use the design skills that they’re learning in school, but then talk about it with other students and other disciplines. That’s a big part of the job of an architect, it’s being able to collaborate with those across fields, so developing those skills is really valuable.”

Apart from simply being aesthetically-pleasing, the prototype had to serve a practical purpose: protecting the rights of a vulnerable population.

“The law students cared more about the rights of these users, what our designs would do in order to reinforce these rights or to establish a form of accountability within these institutions,” said Lanzer. “So it was pretty interesting to see. They weren’t satisfied with just a couple of ideas. It was like, ‘Okay, well, that would affect them this way. How can we make it more perfect? Or how could we make it more feasible?’ We’re so used to being artistic, we can break all these rules, but then our teammates were like, ‘This has to be feasible—and affordable.”

Though the homelessness crisis has touched most corners of the country—with 17 out of every 10,000 people in the US experiencing homelessness in 2019, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness—it’s an issue close to the hearts of those who call the Bay Area home.

“We’ve been thinking about design solutions to the problem for a couple of years now in the program, and obviously as people who live here in the city, it’s something that you don’t really ever stop thinking about,” said Bowes. “Working with students outside of our school with the same goal of tackling the problem provided a lot of insight.”