Director Lulu Wang opens up about her newest feature film, “The Farewell”

By Nina Tabios

In 2016, Lulu Wang first told the truth of her family’s lie on the popular weekly radio show, “This American Life.” It unveiled an intricate tale: Wang’s Nai Nai, or grandmother, was diagnosed with cancer. But as is customary in Chinese culture, Nai Nai’s sons and the rest of the family opted to not tell her. Instead, they planned an elaborate fake wedding—Wang’s cousin’s—for everyone to say their final goodbyes to the matriarch.

As a Chinese-American, Wang grappled with this decision. “Isn’t it wrong to lie?” asks Billi, Wang’s fictional stand-in and protagonist for her second feature film, “The Farewell,” a dramatized version of that same fib out in theaters on Friday, July 19, in San Francisco. Nai Nai’s doctor reassures Billi in English, “It’s a good lie.” Though conflicted, it solidifies for Billi the difference between Chinese tradition and her American upbringing. In the States, such a lie would be cruel, illegal even. But there’s also no going against family, especially under the watch of her elders in China.

Academy Art U News spoke with Wang during a recent press stop in San Francisco, who discussed at length how turning this personal story into a film was a roller coaster of a process. The director takes pride in what the film has been able to achieve with a tight budget and an even tighter schedule, all while upholding integrity in her story with the help of a kindred connection with rapper and actress Awkwafina taking on the role of Billi.

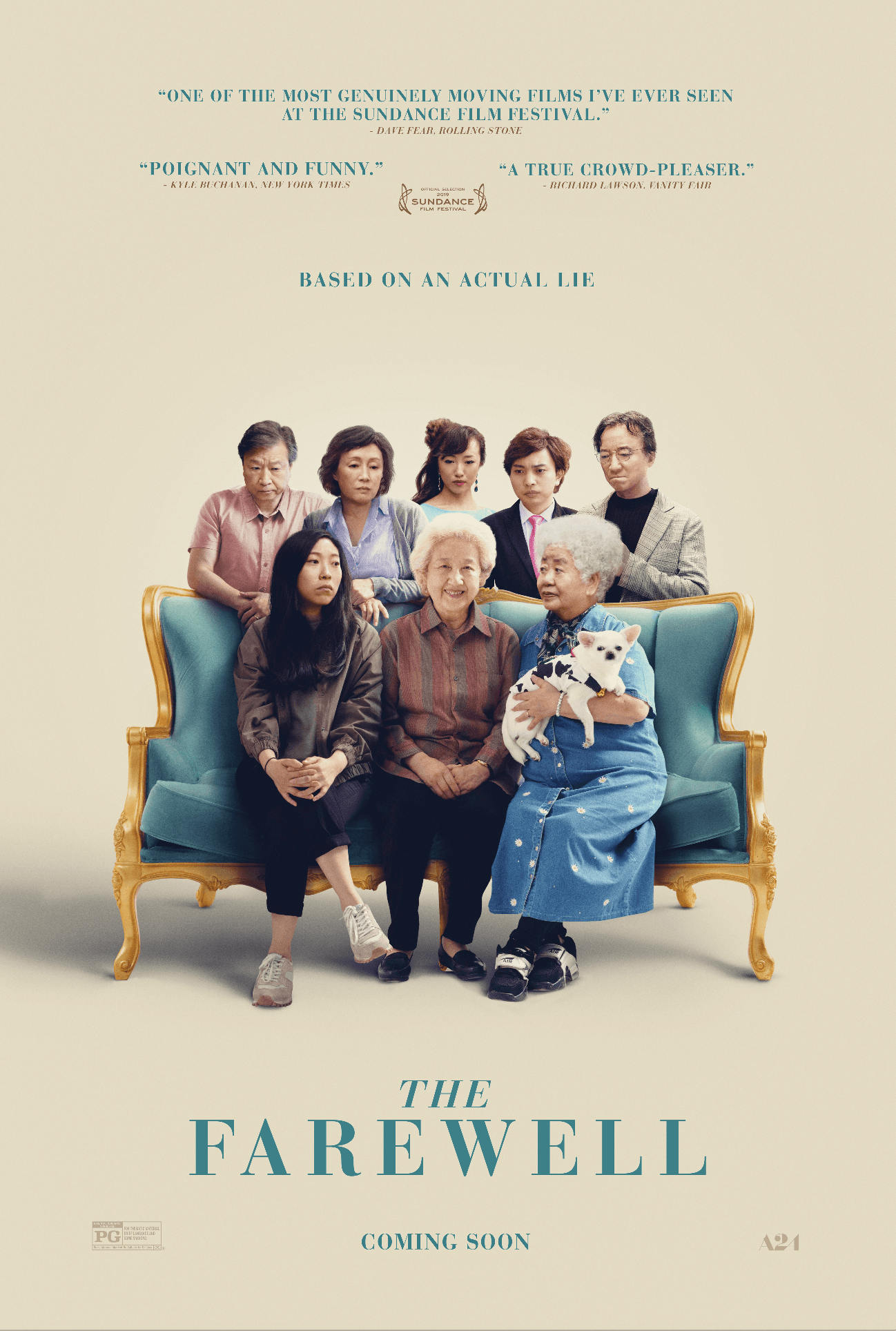

Image courtesy of A24.

You filmed the movie in Nai Nai’s hometown of Changchun in northeast China. What was it like for you to go back there and film?

It was really emotional because these are places, in a way, that I only saw. Other people in my life, like my friends or the American side of my life, didn’t intrude upon that world and so it was really interesting to have this intersection of the two worlds that I’ve navigated through and negotiated between all my life, and to have my non-Asian producers come to my grandma’s hometown and for my grandma and a lot of my family to meet my producers and to actually see me working on set.

You and Awkwafina both have this shared experience of being really close with your grandmothers and experiencing China as westerners. Did that help your relationship as director and actor?

I think that she didn’t really need any kind of real direction because she’s really lived this role before. And it’s very real, it was very prevalent in her life. So I just told her that she didn’t have to play a role, she didn’t have to play a version of me because I didn’t want her to imitate, or create an imitation of my behaviors, the way I talk or anything like that. It was more about these emotions of both being an adult who has an independent life and friends and this entire life in America but then coming back and in many ways returning to your childhood, being seen with your grandma as a little girl again. And where you feel almost like you never left. So that was really the only direction I gave her, to bring in her own experiences to every scene.

How did you go about translating the “This American Life” version of the story for film?

There were a lot of scenes that sort of haunted my memory from my experience and so there were almost these sort of silhouettes that stuck in my memory that weren’t necessarily scenes that were moving the story forward but they were emotional set pieces for me. One of those was the walk and talk with the uncle at night; it stuck out because there was this sort of dreamlike feeling and a very surreal feeling of checking into a very unknown hotel, having my uncle tell me all of the things I’m not allowed to say, all of the secrets I have to keep. I always knew it was going to be a scene and I wanted to protect that scene for what it was. It doesn’t move the story forward, it’s not a necessary scene, per se, but it added to the overall texture. There were a lot of scenes like that, where I knew that I wanted to keep all of that intact in order to give the film texture.

Was the conversation you had with your uncle on the east versus west perspectives real?

That was actually loosely based on a conversation I had with my uncle. We were in China prepping and my uncle was visiting, and so throughout that process, I kept digging deeper to ask him why he and the family still feel like this was the right decision and he gave me that speech. I always wanted to be respectful to his character in the movie and during that time when we were going through with it, I don’t know if I would’ve had the wherewithal to even ask those questions because I was just trying to process my own feelings. But years later, and now I’m working on a piece, I was able to ask those questions. And he was also much more eloquent in expressing himself.

That conversation specifically takes place in a discreet place, but I couldn’t help but notice that food and shared meals set the stage for other key moments. Can you talk about how food played a crucial, if not subdued, role in the film?

I think that food plays a very vital role in Chinese society and any society really where family is the defining unit. And it’s about the collective. It’s around the table where everyone comes together, so it was actually difficult to avoid having meals and food because that’s where the majority, realistically, a majority of things happen where people are talking or trying to avoid talking about things. I really use food as a way also to have a visual representation of the lie and the tension. Because the way that Nai Nai expresses her love is by making food. And the way she wants you to express love is by eating it. But the rest of the family is grieving and not celebrating. The thing is that they’ve lost is their appetite. And so it was the tension of being offered food and not wanting to eat but not wanting to show that you don’t want to eat it. It was a way to visually express how people were trying to hide their real emotions.

Can you speak a little bit on what this film means to you in terms of representation?

I set out to make a very specific film about my family. That means it’s Chinese-American—it has Chinese language so it’s subtitled, it also means that there’s Chinese-Americans who don’t speak Chinese very well, so there’s an array of characters—did I set out to make specifically a Chinese film or an American film or even an Asian-American film? I didn’t. I don’t think I did that … consciously any more than a white director who’s making a film about their family is setting out to make a specifically white film. I think that when you’re inside of an experience, inside of a culture, you’re just speaking from your own experience and your own heart. You’re not approaching representation for the sake of representation. And so I think, to me, it’s really about inclusion. It’s about including voices and asking people questions. Asking artists of color and women who have traditionally not had their voices expressed. Asking them what is your experience like and how do we tell your specific story? And through that is the way to find the true form of inclusion rather than making assumptions.

What are you most proud of when you see this film? What advice do you have for young filmmakers who seek to create unique, authentic stories?

I think that my DP and I, especially, and my production designer as well, the three of us really, really worked hard for the specificity of storytelling. And we worked really hard to create a cinematic language for the film which is particularly difficult to do with a very limited budget, very limited schedule. But we still wanted to make cinema. We wanted to make something that was inspired by some of the great filmmakers that we love. For example, Mike Lee is one of the filmmakers I love and he gets to work and rehearse for 40 days or more with his actors. He spends time with them in a room for 40 days before he even starts shooting in order to get the chemistry right. What I’m proud of is we wanted to achieve those things but we didn’t have those resources. We didn’t have that kind of time. And yet we still pushed for it. And I’m really proud of a lot of the cinematography and blocking and work that the actors did as well.

And I think for young filmmakers, I’d say 90 percent of the time challenges can and often do end up working out better because of these kinds of limitations. You have to get everybody on the same page and it forces you to think creatively outside of the box. But that also makes it exciting. I had a lot of fun doing it.

“The Farewell” opens in San Francisco on July 19.