By Greta Chiocchetti

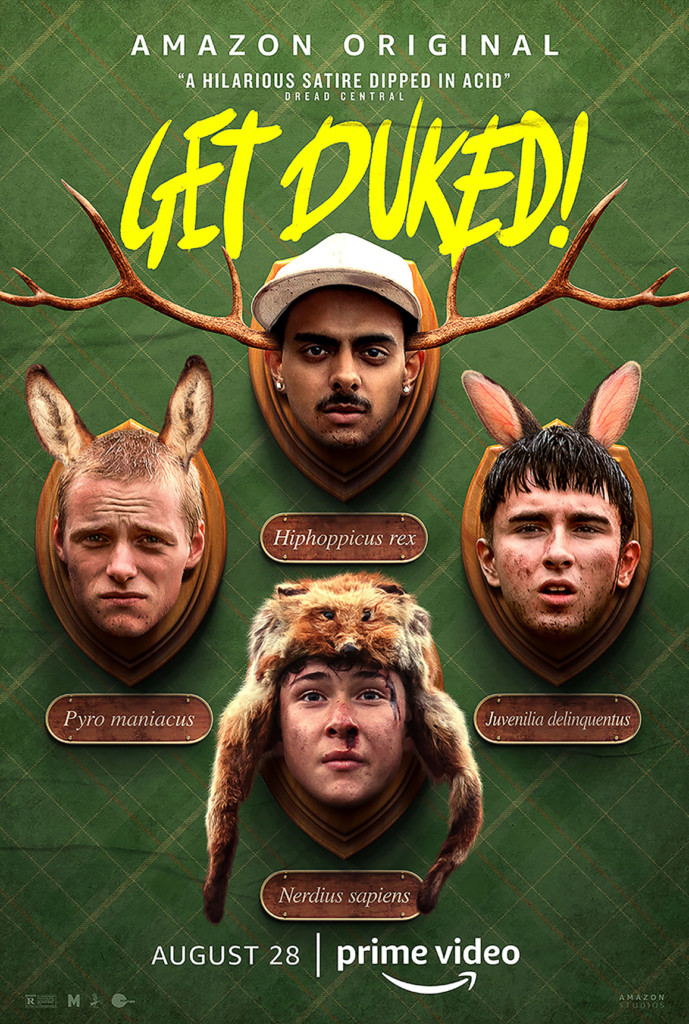

When Scottish filmmaker Ninian Doff began writing his first feature film, “Get Duked!,” he set out to create a satire responding to the generational politics he observed taking root in the UK as well as around the world. The resulting comedy-horror flick, set in the ethereal backdrop of the Scottish Highlands, follows three “troubled” teens—Dean (Rian Gordon), Duncan (Lewis Gribben), and William, who prefers to go by DJ Beatroot (Viraj Juneja)—who are forced to complete an outdoor adventure challenge (based on the real Duke of Edinburgh program, established in 1956) as punishment for their delinquent antics at school—like blowing up a toilet. Overachieving loner Ian (Samuel Bottomley) tags along on the trip, and left to fend for themselves in the wilderness, the boys quickly realize that there is a dark presence following their every move.

The film, which takes cues from comedy classics like “Superbad,” manages to incorporate some big-picture themes in its message while still including punchlines about psychedelic rabbit sh—.

“It often feels like films are either supposed to be gritty and miserable and set on council estates, or just funny and jokey—and not allowed to be anything other than that. I’ve always hated this distinction,” said Doff. “I feel strongly that if we’re going to engage the next generation, we need to make protest movies that don’t feel preachy. Before I even wrote the script, I knew I wanted to make a movie you could watch on a Friday night with your friends, something as quotable as any good comedy, but also feels like a political awakening.”

Ahead of the film’s global release on Amazon Prime Video this Friday, Art U News chatted with Doff, Gordon, Gribben, Juneja, and Bottomley about the film’s “stick it to the man” attitude, the cast’s naturally irreverent chemistry, and the influence of American hip-hop.

Ninian Doff

One of the most interesting parts of the film is the stark contrast between the majestic backdrop of the Highlands and the sound of American hip-hop. Can you talk about your process of selecting the film’s soundtrack and working with composer Alex Menzies on its original score?

I’m from Scotland, and I grew up in Edinburgh. So, this beautiful medieval city basically in the Scottish Highlands is a beautiful example. When I think about the relationship of music to location, it’s normally very literal in cinema. You put bagpipes with the Scottish Highlands or you put banjos with the south in America. But growing up and today, when I’m in these locations, I’m listening to American hip hop in beautiful ancient European countries. So, I always wanted to put a big hip-hop influence into the Scottish Highlands, which is such a crazy clash that strangely worked so well.

So, there’s the actual music from Vince Staples, and Run the Jewels and Danny Brown. And then there’s also a score, which is a mix of culture clash. And same as the film, really, we’ve got S Type, who’s a Glaswegian hip-hop producer, putting in more beats like that. And then a guy called Alex Menzies, bringing in what was more influenced by like a traditional cinematic score, and they actually meet each other at some point in the middle and reference each other, but in a very subtle way that only a nerd like me would really appreciate. But, you’re kind of playing the generational mixing, even at the score level, where we’ve got the old Hollywood score and hip-hop score actually bouncing off each other.

You come from a music video background. In what ways has that influenced the way you direct a feature film?

I come from music videos and I love music videos. Maybe about eight or nine years ago now, with music videos suddenly starting to have a sort of Renaissance, loads of really creative ideas started appearing and became a really great place to experiment in storytelling. I made music videos, not in the traditional sense in the least. But I was able to play with three-act structures and different genres, make a sci-fi and make a musical … And really build a style that way through music videos. So, that actually led to people taking the leap of faith to make a feature, they could see it in the music videos.

And then when it came to making the film from that, instead of being ashamed of the music videos saying, now I’m a serious filmmaker, instead, I kind of wanted to write a little love letter to music videos.

How important is it to you that your first feature film is set in your native Scotland?

I’m from Scotland, from Edinburgh, but I’d been living down in London in England for probably about a decade already at that point, but as I came to writing what was going to be my first film, I felt a really strong urge to go back home and hear the accents of like my childhood and reference that, and I think that’s an interesting thing. Maybe that’s a natural voice that you can more easily write in and that you know by heart and maybe that’s a sort of helpful thing for people to think about. It definitely was for me—a really inspiring assignment to revisit that and get to move back up to Scotland and shoot the movie.