By Kirsten Coachman

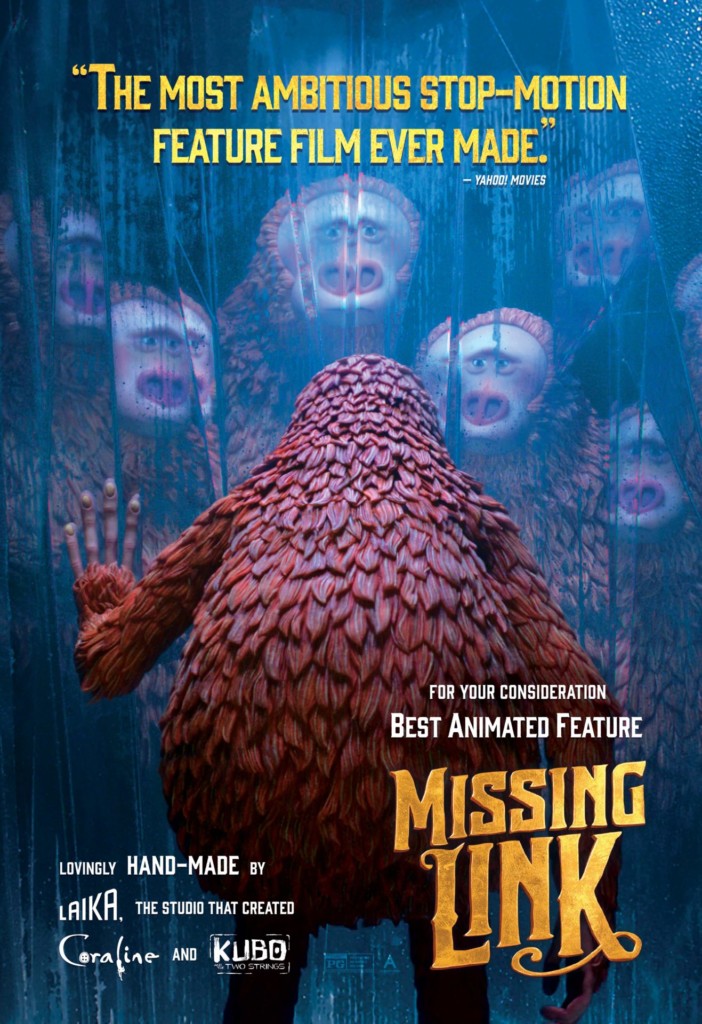

In Laika’s “Missing Link,” written and directed by Chris Butler, audiences join adventurer Sir Lionel Frost (Hugh Jackman), a lonely Bigfoot dubbed Mr. Link (Zach Galifianakis), and the fearless Adelina Fortnight (Zoe Saldana) on their journey to Shangri-La, as Mr. Link desires to find community among his fellow Yetis. The stop motion animated feature is quite the feat, as “Missing Link” took upwards of five years to complete. The bright and bold film contains complex action-adventure sequences that are a pure delight to watch unfold on screen.

Additionally, “Missing Link” made quite an impact on awards season. It picked up eight Annie Award nominations in December, tying with “Frozen 2,” took home the Golden Globe for Best Animated Feature Film in early January, and is nominated for an Oscar.

This past December, Academy Art U News sat down with Butler and “Missing Link” producer and Laika’s Head of Production Arianne Sutner to learn more about the process behind the making of their award-winning stop motion animated film.

So first off, congratulations on the Annie Award nominations.

Chris Butler: Oh, thank you.

What does it mean to have the film recognized?

CB: Awards season stuff for me is always such a different feeling from when the movie first comes out. Because it’s your peers, it’s being acknowledged and appreciated, and that feels good, because making an animated movie, you’re kind of hidden away in a dark room, or dark rooms, for three, four, five years and you don’t really have much contact with the outside world. And because we’re in Oregon as well, we’re not in the center of the industry. We are a little bit removed, so it’s nice when the people that you look up to, your peers, your fellow artists when they’re appreciating you that that feels good. And that’s what the Annies is really. It was a thrill, actually, ’cause I wasn’t expecting this to get that many nominations.

Arianne Sutner: Honestly, we were thrilled, I’m thrilled, this movie, awards season, it’s another chance for us to be able to go out and continue to find a bigger audience. And this movie is so beautiful. It’s such a lovely movie, both to look at, and the message and the characters. I like having another go at getting people to see it. And it’s fun to go around and talk about something that you’ve worked so hard on, that you’re representing for all the people who need it. We’re so proud of it.

CB: We get to talk about it. We get to fly to fancy hotels and have chats about our work and that feels good.

Chris, you were originally focused in 2-D animation, what captured your attention about stop motion?

CB: I started out [a] 2-D animator. I knew animation wasn’t really for me. I loved it, but I was more the bigger picture rather than shot by shot. I think it’s a different mindset, to be honest. I wanted to tell the whole story, not one little facet of the story. So, I got into storyboarding and at that time it wasn’t the best time to be in animation. It was kind of the doldrums. I was living in London and most of your work was commercials, which is fine, but you can’t really get your teeth into a story in a commercial. And then the opportunity came up to work on Tim Burton’s “Corpse Bride” as a storyboard artist.

It was a real epiphany for me because, up until that point, it’s just you sitting at a desk and you might have some artwork to reference, but it’s essentially you in a room drawing by yourself. And on “Corpse Bride,” if I was lacking inspiration, I could wander onto a set and I could actually picture where the camera was going to be. I could see the physical puppets. And that is basically like wandering onto a live-action set. You’re in the location, you’re in the moment. It opened my mind up. It also presented me with a whole bunch of limitations because on a stop motion set, you can’t put the camera any way you want. It has to fit. So I started to think more about “why am I cutting to this? Why am I composing this shot like this?” And I think it made me a better filmmaker. It made me think a lot more about the filmmaking process in almost a live-action kind of way.

AS: I think stop motion is really live-action just at a very glacial pace, one frame at a time.

When you’re writing, I know you kind of brewed on both the characters and the story for quite a while, were you focusing on “I have these characters in mind, what do I do with them?” Or was it, “I’m going to work on the story and try to figure out what we’re going to tell?”

AS: I never thought of it like that.

CB: The original seed of this idea was a long, long time ago and I’d been talking about it for years and years and years was like, I want to make like an Indiana Jones movie in stop motion. In that sense, I guess the character did come first and that it was this period action-adventure hero and Sir Lionel is very much based on Sherlock Holmes and Indiana Jones.

So, it’s true, the character did come first, but then the story itself, that was the other side of things. That was what would happen if Bigfoot was lonely and heard about Yetis and wanted to go and find them. And I kind of meshed those two ideas together. You know, Indiana Jones adventurer and lonely Bigfoot. And that became the story. So yeah, the characters did actually come first.

Which scene going into it did you think was going to be the biggest challenge to animate? And what scene wound up actually being the biggest challenge—if it’s different? I would guess the train or the ice bridge.

CB: The ice bridge, absolutely. Writing it, I knew it was going to be the most complicated thing and I think I knew we could do that. And it was also in fewer elements, I think. And we’d done water, I know we hadn’t done it to that extent, but seeing what we did with water in “Kubo [and the Two Strings],” I kind of felt more confident, whereas the ice bridge was something entirely new. And even the design elements, we were designing everything from scratch because there is no Yeti culture, there is no hidden secret valley of Shangri-La. But I think I knew when I was writing it that it was going to be complicated. It’s also characters suspended in thin air.

AS: That turned out harder than we even thought it would, but sometimes you’ll come up with something and it’s surprisingly difficult.

CB: (To Sutner) But when you read the ice bridge sequence, you must’ve thought, “Oh…”

AS: Well, I did. And I did think the same thing, like we did water, but it was really that moving of the ship. Just in general, not complexity necessarily of shots, but he writes an action-adventure movie and he shot it like an action-adventure. It’s very, very cutty and all of that proved really challenging with our schedule and the fact of our puppets are getting done at different times. Sometimes that factors into it, too. But honestly, that whole script was pretty challenging.

CB: Even two characters talking in a room on this movie, it was difficult. As an example, the scale of these puppets was different because our main characters are adults. And the optimum size for a puppet is 12 to 13 inches.

But also the design of the characters had smaller heads than we’ve done before. And bigger heads allow for more mechanics in the head. So we had all kinds of problems with how to get the eyes close enough together so that they would match the designs. Stuff like that I don’t think about. I’m just like, “I like this design.”

AS: Since we didn’t have kid [characters], we were like let’s make the adult puppets the size of a kid puppet and scale it accordingly. Because every time you scale up in miniature, it becomes bigger and bigger and more unwieldy and more expensive. But it proved to make the eye rigs really tiny and all of that. However, we, at the peak, had 95 units going. If we had made it any bigger, we would have had to find a new warehouse.

CB: As context, 95 units—we normally aim for about 50 to 60.

For units, are we talking puppets?

CB: We’re talking about areas that are curtained off that you’re shooting a shot.

Oh okay, so sets?

CB/AS: Yes!

AS: Imagine you’re going to a studio like Pinewood … at its glory, at its peak and everything is inside. These are like sound stages, they’re cordoned off by these big, thick black guillotine curtains and everything is the same, except we’re not shooting sound, but we’re shooting live on all of these different units. People walk miles a day from one unit to the next.

CB: That’s why we have so many duplicate puppets because we’re shooting Mr. Link here, here, here, here, here.

I read that it would take days to set up a shot, I didn’t realize you also had multiple shots going at the same time.

CB: Yeah, we had to. On this movie, as an example, maybe we’re shooting the bar scene. We need six puppets for a shot, but we’ve only got four of them. We’ll shoot part of it against green screen and then six months later when that puppet becomes available, we’ll shoot that. We’re constantly juggling the schedule and puppets and sets.

How does that affect your pipeline when you have multiple units running? If you have 95 units running, is that 95 different pipelines also going?

AS: We have unorthodox pipelines.

CB: That’s for sure.

AS: Yes, because we have characters, they’re puppets, there are armatures, which we build and design and machine and make in-studio. And then the faces have a different pipeline because they are getting animated in Maya and then these assets are being printed out.

So, there’s like two separate things going at the same time. We’ve been there now for like 14 years and we’re trying to get better and better at taking these two different pipelines and merging them into one puppet and everything gets in the way of all of our best-laid plans because if something is late, we’ll go to Chris and say, “Hey, can we shoot this? We have the voice for it, we have this for it.” And he’ll say any number of things. But it changes all the time.

CB: Yeah, you have to be adaptable. But I think what you said, probably from my point of view, watching it as a director, is the most important part is that when the best-laid plans fall apart and being able to think on your feet is far more important than someone who is locked to this digital schedule that they spent weeks making; they have to be prepared to throw that out.

Touching on collaboration, you had a lot of moving pieces. How do you go about maneuvering everything to get to your final product?

CB: Well I think it does help that a lot of us have worked together now for five movies. And so there are certain key people. As a director, it’s vital to know that you can lean on people and you don’t have to either micromanage them or tell them how to do their job. That’s the scariest thing for a director is when you’re entrusting this huge idea with somebody and you need to have absolute confidence that they will realize it, no matter how problematic it might be. And there are definitely those people who I would trust with anything and I have to. And having a shorthand with those people is great. We’ve worked together so long that I think that’s a really solid basis to make one of these things.

Last couple of questions: being that you’ve been able to accomplish so much, especially with “Missing Link,” what do you think is the biggest misconception about stop motion? And what advice would you give our students at the Academy?

AS: A big misconception is that [stop motion] is more expensive than other forms of shooting. It is not. It is not more expensive than CG, it is much less expensive.

CB: I do think a misconception with stop motion is that it is this nostalgic novelty that has to sit in the past and it doesn’t. It should evolve like any other medium and that means you should be able to use whatever tools are at your disposal. In the end, what you’re trying to create is a beautiful image on the screen and it doesn’t really matter how you got there.

I think advice for students is—I hear a lot from students who are interested in stop motion but they’re not focused on what aspect of it they’re interested in. No point going to a studio and saying, “I want to work in stop motion,” ‘cause they’ll say, “What do you want to work in? The costume department? Do you want to work in the art department?”; so for all students, I would always say focus your portfolio and work on the types of material that will benefit you when you go to an interview.

AS: That’s incredible advice. Also, I want to say to your young women: storyboard, you can direct. Go out there and get it and put your stories out there.

CB: For sure. It’s always been such an old man’s industry and it needs changing.

AS: And also people of color, anybody can do this. If you’re a filmmaker and you enjoy this kind of thing, come and do it. Study, practice it, and do it.

“Missing Link” is available to stream on Hulu.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.