By Nina Tabios

One of the perks of studying landscape design at the Academy of Art University is that students learn in the heart of a constantly changing San Francisco. While most development projects have an experienced team mapping out the master plans, the School of Landscape Architecture’s (LAN) immersive design studios place students in the driver’s seat to reimagine the city’s transformative spaces.

This semester, a group of undergraduate and graduate students in Director Jeff McLane’s LAN 498/695 Habitable Cities class took on one of the city’s largest projects to date, the Potrero Power Station. Earlier this spring, Mayor London Breed approved the redevelopment of this 29-acre complex along 23rd Street, which consists of 2,400 housing units and over six acres of public parks, recreational areas, tourist attractions, and waterfront access to the Dogpatch neighborhood.

“This is the most complex studio we’ve ever run,” McLane said. He explained that the site was very complicated. Of the 29 acres of public and private-owned land on the waterfront, there are seven acres of public open space, which meant regulatory agencies like the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), the Port of San Francisco, and the planning department had to be involved.

“A lot of people from those agencies came in and talked to the students,” McLane added. “The great thing about the Zoom class because was that it made access to different perspectives easy, and that was a big thing. There was this kind of real-world feedback.” The students also received feedback from the City Historian, the developers of the site, the SF Parks Alliance, as well as the landscape architects working on the project.

One of the professionals McLane invited was John Francis, a project manager with the housing delivery team in San Francisco’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development. Having spent three years finalizing the Power Station master plan, Francis had a wealth of knowledge on the processes and protocols that go into planning a site of this magnitude.

“Urban design needs to be influenced by policy decisions that get made before a project even is approved,” Francis said. He explained concepts couldn’t just be beautiful; they had to be profitable for developers, follow regulatory constraints and codes set by the city, and be considerate of the concerns of the parks’ alliance and surrounding communities.

“That’s ultimately the point of the design studio,” Francis added. “To take all of this information that you’ve gotten from exterior sources and synthesize it into something that reflects your own understanding and values as a planner or designer.”

Students could refer to the Design for Development document, or the D4D, which outlines how the site is developed. Fortunately, students also got to hear from the very person who sketched out the final site plans, Plural Studio Co-Founder and Principal Designer Haley Waterson, to gain a firsthand perspective on how to balance various elements.

“The students really had to download as much as they could, to at least absorb the pieces of the open space, understand the building massing and use, which takes quite a bit of time,” Waterson said. “In general, understanding the scale of the whole development was really challenging and each student found their own way through it and responded to it differently, and that was interesting to see.”

By the final class review on Friday, Dec. 18, 2020, when all the work was virtually pinned on the online platform Conceptboard, students delivered site plans that pushed their design process to the limits.

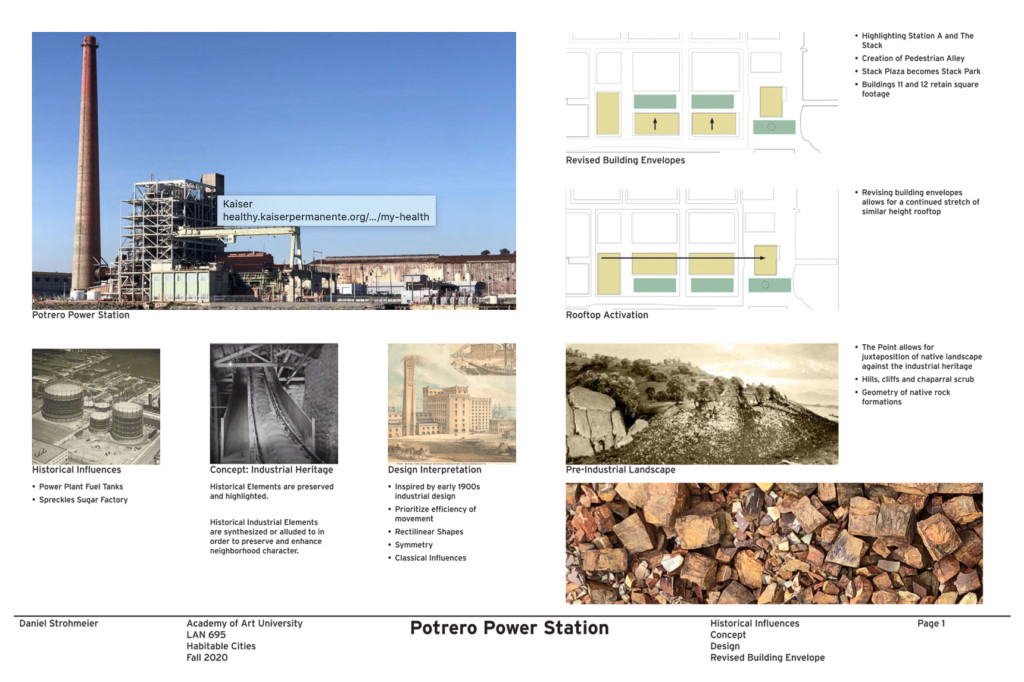

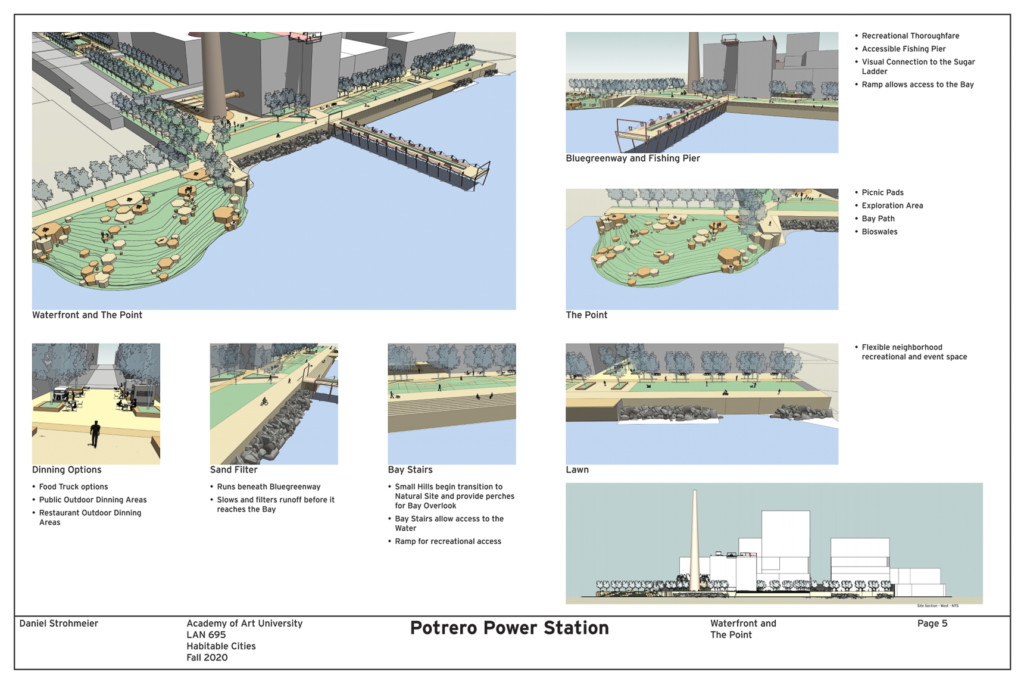

Graduate student Daniel Strohmeier wanted to preserve the Power Station’s rich industrial history in his community-oriented master plan. Elements throughout the site hinted at the power plant and sugar refinery that once stood in the area; elsewhere, various plazas and paseos brought in plenty of green.

“I really wanted to bring in that neighborhood character,” Strohmeier said. “The efficiency of industrial architecture was the real inspiration of the site because what we’re doing is really embracing the leftover elements, like the stack building.”

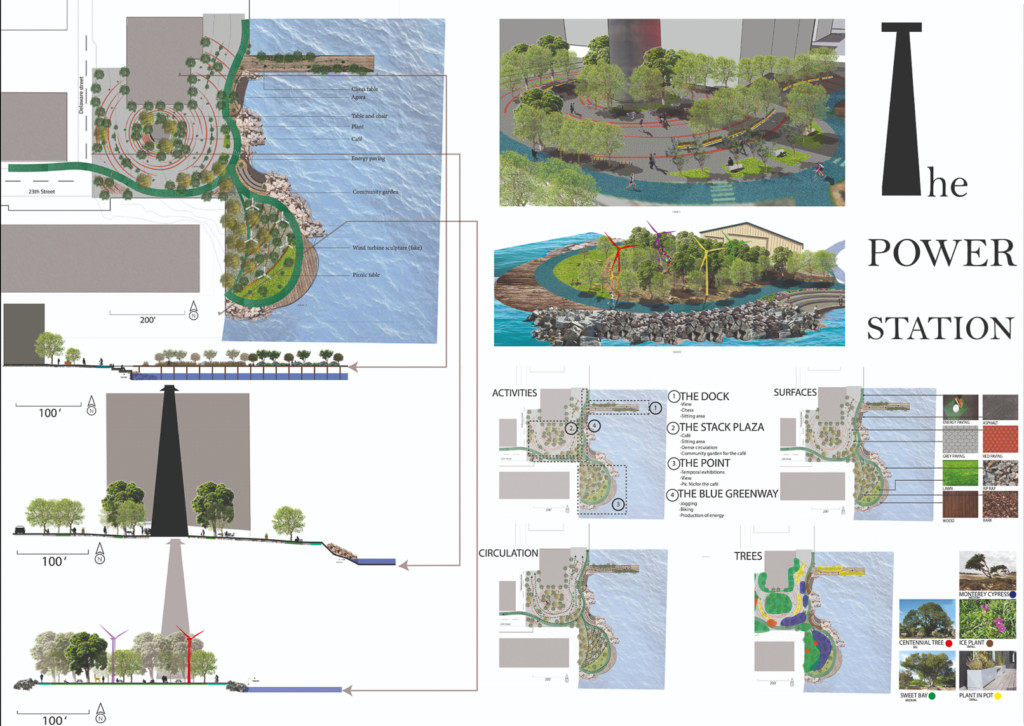

Power and energy were a common theme, and Charlie Messai, another graduate student, applied his interpretation to the stack plaza. Like many of his classmates, Messai had to go back to the drawing board before fully settling on a concept but his persistence paid off when he delivered an effective ripple illusion in the pavement that directed foot traffic to areas where they could sit, hang out, and enjoy the view of the waterfront.

“I initially had a lot of ideas, but through this class, I learned how to approach a project by starting with the basics,” Messai said from his home in Paris, France. “You have to create something functional first. When you’re designing a plaza, it’s so that people can use it and have somewhere to go to every day, to take a break from work or be with their families.”

For undergraduate student Christie Choy, it was important to create balance within the space. Like Strohmeier and Messai, Choy paid tribute to the site’s past but also wanted to look toward a more sustainable environment, which meant restoring the natural shoreline habitat and installing suitable programming for nearby families and children.

“This site is basically a whole new neighborhood they’re building in San Francisco,” Choy said. “For this project, I wanted to lay out functionality and find elements that tie them together into a concept. Consistency and balance are [some] of the most challenging things but studio projects like these help us think through our design process and find the right, or most sensible, solution.”

The particular design studio was the first-of-its-kind for many reasons. McLane explained that mixing undergraduate and graduate students together produced a unique result. Although they presented individual concepts, students discussed, collaborated, and problem-solved together throughout the process.

“Having everyone together and working together toward the same goal pushed their skill levels,” McLane said. “They were constantly confronted with their own limitations, which is how you learn. There’s a rigor to design that you have to establish in yourself to be successful, and I think they did that.”