By Nina Tabios

Before Peter Schifrin was building larger-than-life sculptures in various parts of the country, he once was an elite fencer competing for the U.S. Olympic team at the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles.

The team placed 12th that year. It was an indicator that Schifrin’s time with fencing—he spent nearly a decade competing for world and national cups—was over and shortly after, the instructor at Academy of Art University turned his attention to building out a career in sculpture. But almost 40 years later, Schifrin received another shot at an Olympic honor.

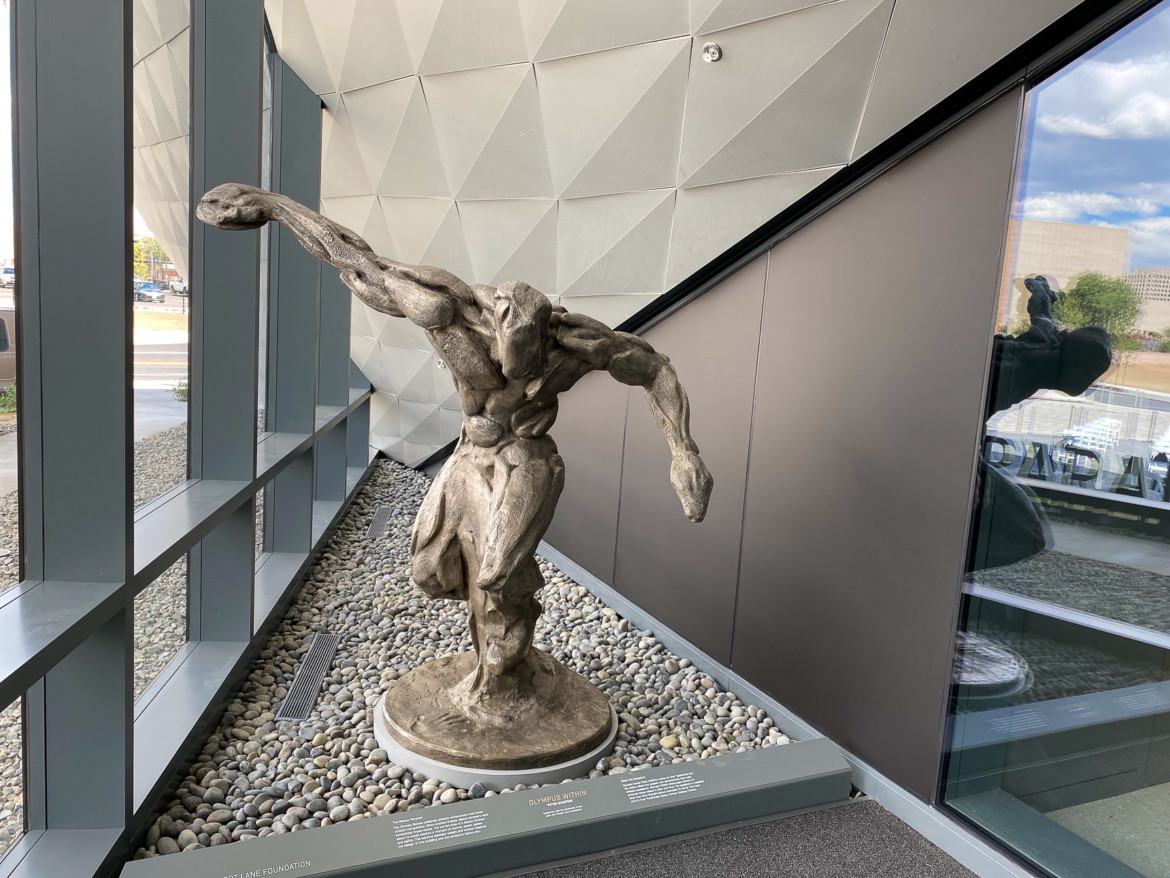

Earlier this summer, Schifrin packed and shipped away a monumental sculpture to the new U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs. Schifrin’s creation, a six-foot-tall, 400-pound bronze behemoth titled “Olympus Within,” will greet guests at the newly opened 60,000-square-foot interactive museum where they can learn about the Olympians and Paralympians that competed for Team USA throughout history. As it stands next to the museum, Schifrin hopes all guests, athletes and non-athletes alike, will feel inspired by the sculpture.

“The role of this monument was to inspire. It’s to remind people you can do better, you can be better, follow that dream and be the powerful person you are inside,” Schifrin said from his home in Santa Rosa. “Not everyone is an Olympian, but everyone has within them that desire to be excellent in something.”

The museum was designed by award-winning architect Liz Diller, whose concept takes after the grace and movement of a discus thrower. Inspired, Schifrin decided to model “Olympus Within” after his idol, the great Al Oerter, who wasn’t just a four-time gold medalist from 1956 to 1968, but was an athlete turned artist too. In fact, it was Oerter’s wife Cathy, who reached out to Schifrin with the opportunity. It was definitely one of the most serendipitous commissions of his career, to date.

“[Oerter] really believed [in] the principles guiding Olympism, or being an Olympian, that idea of discipline, focus, and passion,” Schifrin said. “So many of those things that an athlete who performs well needs, [such as] having goals and sticking with it, are similar to the same principles that an artist needs. There’s a lot of things in common.”

Instead of creating the form after his physical likeness, Schifrin wanted to emulate Oerter’s performance. He wanted to capture Oerter’s essence and sheer might. “They do this kind of spin, [it’s a] dance and throw that Olympic discus throwers do, and I made these energetic, three-dimensional sketches that look very spontaneous,” Schifrin said. He put together three different 12-inch clay models for the museum to choose from, and it was a no-brainer that they selected the mid-throw pose.

“It’s not meant to be a portrait of Al Oerter, it’s meant to be inspired by his movement, his power,” he continued. “I was trying to create a heroic scale, this idea of human energy contained and your potential, like what you could be.”

Schifrin found sculpture in high school, when one of his teachers encouraged him to keep trying even though, like most beginners, he struggled at first. He liked working with his hands and when he wasn’t competing as a four-time NCAA All-American for San Jose State University, Schifrin was sculpting. Compared to the rigors of the sport, he felt a different kind of joy in this pursuit. Art was fun—it allowed him to be expressive; it was play as opposed to competition.

But when he was finally able to give art his full attention, the transition from an athlete to an artist wasn’t always easy. After he completed his bachelor’s degree, Schifrin enrolled at Boston University for the master’s program in sculpture. Just like in sports, there were doubters and naysayers as Schifrin chipped away at school. But he kept at it, eventually getting commissions for public and private collections from the Bay Area to New York. In 2017, Schifrin and David Duskin, his fellow sculptor and Academy M.F.A. fine art—sculpture alumnus, were hired to create a life-size bronze monument of TV producer and political activist Norman Lear—which stands in downtown Boston at Emerson College.

Now, as a teacher, Schifrin hopes to impart his experiences as an athlete and artist to his students. The biggest lesson from his two careers? Master the rules so you can break them.

“We’re given rules, some structure, and these principles. But guess what, you’re going to have to make your own [because] that’s what artists do,” he said. For student-athletes at the Academy, Schifrin relayed that the lessons he learned from physical discipline gave him the confidence to trust his path and vision. “When you make that painting, no one has ever made that painting. When you jump that new height or hurdle record or the high jump record, no one has ever done that before. You’re taking risks and you have to trust yourself.”

“Athletes are performers and you get to watch them perform. But the famous painter Chuck Close said, ‘Every painting is a performance too,’” Schifrin said. “You just don’t get to see the performance.”