By Isabella Cook

On Oct. 27, concept art and illustration icon Tim Flattery joined Academy of Art University’s School of Visual Development (VIS) to discuss his impressive portfolio of work that spans over two decades and share insights on the process of designing for film.

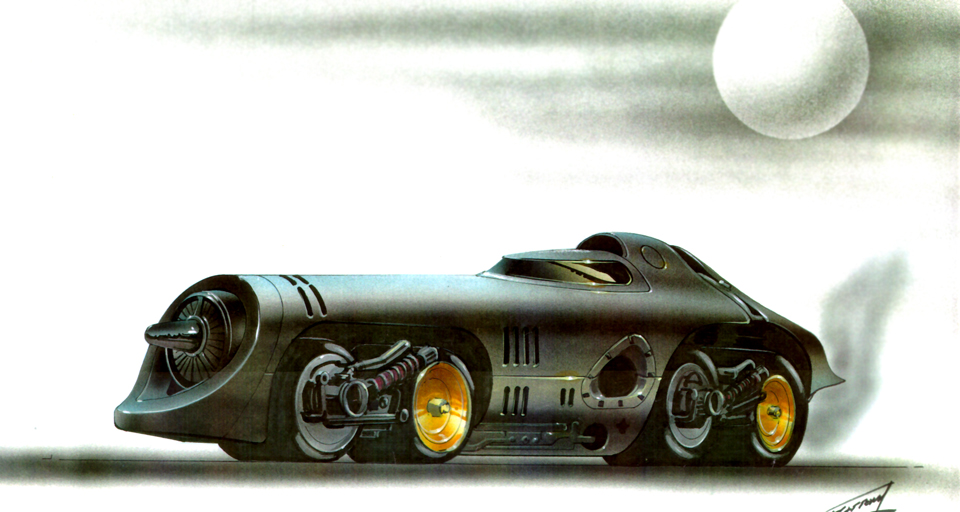

Flattery is known for creating concept illustrations for the Batmobile in “Batman Returns” and designing the Infinity Gauntlet for Marvel’s “Avengers: Infinity War.”

“You know you have one of the best designers in the industry when you can’t remember all the movies he’s worked on,” said Executive Director of VIS and 2-D Animation and Art Direction Nicolás Villarreal.

Some of Flattery’s noteworthy projects include “Back to The Future: Part II,” “Child’s Play 3,” “Saving Private Ryan,” “Men in Black,” “The X Files,” and a host of Marvel movies, including “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2,” “Avengers: Endgame,” and “Captain Marvel.” Most recently, Flattery completed concept art for “Thor: Love and Thunder” and “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.”

VIS Associate Director Christopher Carman added, “You guys are very, very lucky that Tim was able and willing to join us to share some of his incredible background and experiences. I mean, it’s daunting.”

Following introductions, Flattery began his presentation by taking Academy students back to the start of his remarkable career. “I should start by saying, like all of you, I started off in art and design school myself back in the ’80s,” said Flattery. “I was always interested in storytelling and movies, but my degree was in industrial design because, back then, there wasn’t a career path of concept design or concept artist—it wasn’t heard of.”

After finishing his education and moving out to L.A., Flattery got his start in 1987 working in the film design industry with a movie called “My Stepmother is an Alien.” Flattery described the movie as “his break” into the industry, which led to working on “Back to the Future Part II.”

“I have about a hundred movies under my belt now,” said Flattery. “[IMDB] doesn’t even list all of them.” Flattery shared that throughout his film career, he has worked on everything from “hardware to architecture to characters.” However, he is primarily known for his hardware, citing Thor’s hammer as one example.

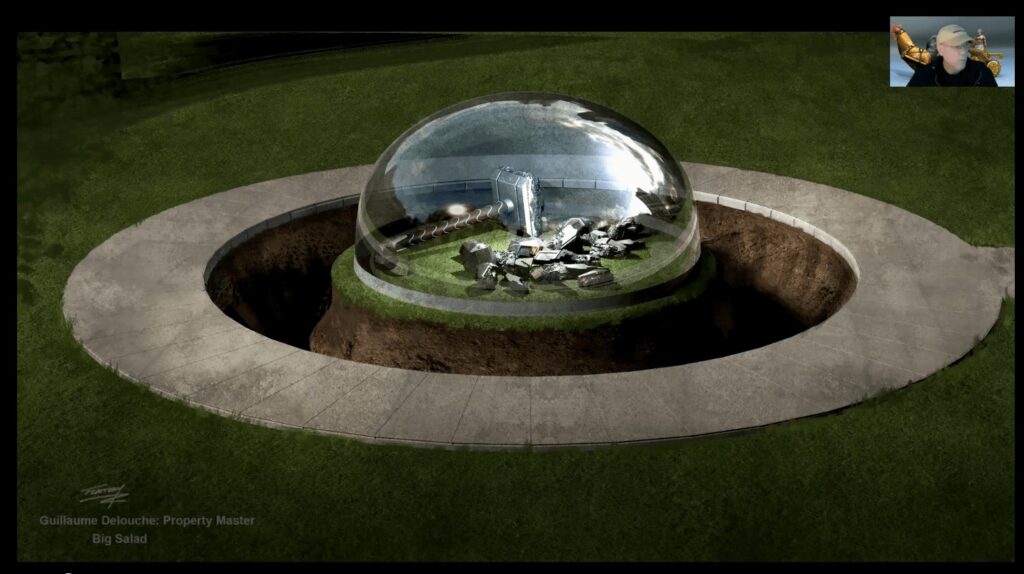

“I didn’t design the original hammer (it was designed in the first ‘Thor’ movie), but it had to be redesigned,” he explained. “[S]o we toiled over each piece that you see in this image (shows an image of Thor’s hammer shattered to pieces) and how it goes back together. What it looks like when it’s together, what the energy looks like when it’s together … I studied literally every crack in this hammer and re-pieced it together. I think I spent two months just on the hammer alone. But, you know, some of these props become their own characters … so all the design time and the thinking and the meetings are appropriate because they’ve got to serve the story. And all this stuff has to serve the story. That’s the first priority.”

Another presentation slide displayed an image from his work on “Thor: Love and Thunder”: a giant rooster pulling Zeus (Russell Crowe) in a chariot. Flattery explained that a third of his work never makes it to the silver screen, including this original concept for Zeus’ introduction in the latest “Thor” installment. “I wish this were in the movie because I’ve never had so much fun in my life,” said Flattery. “So, I keep this in my presentation because some of the throwaway stuff that doesn’t make it into the movies is some of the best stuff that we do.”

Flattery discussed collaboration between artists while briefly touching on the Infinity Gauntlet from “Avengers: Infinity War.” “I had a big part in the Infinity Gauntlet and all the aspects that go into that,” he shared. “There are two or three other folks involved in conceptualizing, modeling, and a lot of this happens from deriving from what was in the comics too.”

The creative team builds from models and data that Flattery provided, including three and four views of his work, dimensions, callouts, and exact details. The endgame, so to speak, is that the person fabricating the work has a complete blueprint to work with. “In this case, it was a real armorer who does suits of armor and is an amazing blacksmith, who made this for real,” explained Flattery. “They go by all these drawings.”

Following his presentation, Flattery answered questions from students in attendance, including the differences a concept designer may experience working in preproduction versus post-production. “Even when a movie is in development, concept designers, it’s so blue sky, like, anything goes. And then when you get into preproduction, it’s like, this stuff has got to get built and executed on set on a schedule and on a budget,” said Flattery. “And then you’re designing for execution as opposed to just for concept.”

He further elaborated, explaining that designers who work on environments and sets would work alongside various creative teams, ranging from production design and set decoration to graphic design and visual effects.

“A lot of the time with visual effects, you’re designing stuff that they are pre-emptively wanting to implement into the design of the set so they can do their job in post,” said Flattery. “So you’re upfront and uploading in that position.”

For postproduction, in general, Flattery shared that concept designers do a variety of things. Using James Clyne as an example, he mentioned that some designers will get involved in preproduction and have a “design say” in that part of the process.

“But traditionally and historically, [concept designers] were working on designing out the effects of what was happening in a film. And that would include—let’s say, there’s a futuristic city vista, and it would have to be done in miniature—a lot of times that would end up happening in post, being designed in post, as well,” said Flattery, noting designers such as Ralph McQuarrie and others who did that sort of work. “That transitioned into today’s concept designer, as well.”

When asked how one can get their foot in the door working on “blockbuster projects” and if aspiring visual artists need to be a part of a Local 800 since the majority seem to be “union-based shows,” Flattery explained that in today’s film industry, “there’s a guild for everything.”

“There’s the writer’s guild, the director’s guild, the actor’s guild, and the art director’s guild. And within the art director’s guild, which is [comprised of] illustrators, concept designers, set designers, matte painters, graphic designers—pretty much everybody involved in the art department,” said Flattery. “To work on mainstream, studio-based films, you have to be in that guild.”

While being part of the art director’s guild offers different benefits such as health insurance and pension, getting in, he admitted, is tough. Flattery referred to the process as a “double-edged sword” due to needing to be a part of the guild to work on a tentpole film, but you also need to have worked on a film for 30 days to get into the guild.

“Get known. Get yourself out there—social media, ArtStation, start to network,” advised Flattery. “Most of the folks working as concept designers in the film industry now, this is the way they’ve done it. They didn’t go knocking on doors like you’d have to back in the day. They got known through the internet, and the film world came calling on them because of that, and then they worked out getting in the guild from there.”

To watch Flattery’s full presentation, please visit: video.academyart.edu/media/Design+with+Tim+Flattery/1_ta9hgpcr/206525813